Viking Objects

Needle (CM. 1844-2008)

A cylindrical copper-alloy needle with a circular eye punched into a flattened section. Needles were a common textile tool and could be made from bone, metal or wood. They are generally considered to indicate the presence of female craftspeople, reinforcing the view that the Viking camp at Torksey was inhabited by women and children as well as the warriors of the Great Heathen Army.

Read More

Viking Objects

Copper-Alloy Ear Spoon (CM_1849_2008)

This copper-alloy ear spoon has a spiral twisted body with a small rounded head. It was found at Torksey, Lincolnshire. Ear scoops (also known as ear spoons) were used to clean out ear wax. They are very common finds on Viking Age sites, suggesting that people took this aspect of personal hygiene very seriously.

Read More

Viking Names

Ullesthorpe

The first element of Ullesthorpe, in the Guthlaxton Hundred of Leicestershire, is the Old Norse male personal name Úlfr (Old Danish Ulf), an original byname meaning ‘wolf’. It was a common name throughout the Viking diaspora. The second element is Old Norse þorp ‘a secondary settlement, a dependent outlying farmstead or hamlet’. The township names that line Watling Street and those to its north-east are predominately English in origin; however, Ullesthorpe, Catthorpe, and Bittesby are the exceptions. It is important to note that although Ullesthope has both an Old Norse specific and generic, Bitteby’s first element is Old English and Catthorpe’s is a feudal affix, which indicate only light Scandinavian settlement in the surrounding area. Ullesthorpe and Bittesby were formally a single land unit which Bittesby was later carved out. Ullesthorpe was likely the dependent village of Bittesby, and now has a narrow reach of land to its west which runs to Watling Street.

Read More

Viking Names

Eindridi

The Old Norse male name Eindriði is mainly found in Norway. It is the first element of Enderby (now divided into Bag Enderby, Mavis Enderby and Wood Enderby) and possibly Anderby, both in Lincolnshire. There is also an Enderby in Leicestershire.

Read More

Viking Names

Heath

The eatlier name for Heath, in the Scarsdale Hundred of Derbyshire, was Lund from Old Norse lundr ‘grove, small grove’. Heath from Old English hǣð ‘heather; a tract of uncultivated land’ replaced the older name which remains only as a field name.

Read More

Viking Names

Woodthorpe

Woodthorpe, in the Scarsdale Hundred of Derbyshire, is an Anglo-Scandinavian hybrid name from Old English wudu ‘a wood; or wood, timber’ and Old Norse þorp ‘a secondary settlement, a dependent outlying farmstead or hamlet’.

Read More

Viking Names

Skalli

Skalli an original byname meaning ‘bald-head’. It is recorded in Western Scandinavian mythology as the name of a giant, it is fairly common as a byname in Norway and Iceland. A few instances are recorded in runic inscriptions in Sweden and in Danish place-names. Skalli is the first element in Scawby, Lincolnshire, as well in several other place-names in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire

Read More

Viking Names

Sibbi

Sibbi is originally a short form of the Old Norse male personal Sigbjǫrn. As an independent name it is common in Sweden and fairly frequent in Denmark, and is recorded in a number of runic inscriptions. Sibbi is potentially the first element in the place-name Sibthorpe, Nottinghamshire.

Read More

Blog Post

Slithering Swords in the Viking World

Reproduction of Viking Age sword from Repton by Adam Parsons Forget Vikings and The Last Kingdom – the most pulsating depictions of Viking Age battle appear in early medieval Scandinavian poetry. Here, armies transform into elemental forces and fierce creatures, clashing together in a mass of noise and light. Popular in this imagery is the likening of swords to snakes, with poets styling these weapons as ‘wound snakes’ and ‘battle snakes’ that bite at their enemies. This was not just poetic flourish. Real Viking swords also had something of the snake about them. Their pattern-welded blades writhe with sinuous designs, their hilts with looping serpents. Scale-like panels encrust the heavy hilts of Petersen’s Type D swords; one from Trælnes, Norway even has dark diamonds on a brighter background, mirroring the dark-on-light streak along an adder’s back. Similar designs were made with inlaid wire on other swords. It is even tempting to ponder whether coiled-up blades in Viking burials evoked the posture of resting snakes. How and why did this union between swords and snakes come about? Well, both are long, thin, bulbous at one end and tapered towards the other; they are glossy with mottled markings; both shed their skin (or scabbard); they weave about and bite when threatened. This would be an elegant explanation if snakes were just ‘snakes’, shall we say; but in Viking Scandinavia, serpents held immense symbolic significance. They permeate Scandinavian cosmology, from the ‘world serpent’ Jǫrmungandr to Óðinn using a snake’s form to steal the mead of poetry. Clearly, poets did not just liken swords to snakes because they looked a bit similar. So, what was going on? Poets often paired snakes with key symbols of power and status in the Viking world, namely arm-rings, gold and ships. Swords behaved similarly in Viking thought, so it is perhaps no surprise that snakes dominate their description and decoration. But the ambiguity surrounding snakes may also have been a factor. In Norse mythology, serpents represented both order and destruction (Jǫrmungandr binding the world together, then running rampant at Ragnarǫk). Similarly, in the poem Rígsþula Heimdallr’s highest born child has ‘piercing’ eyes ‘like a young snake’s’, but in Skirnismál the ‘shining serpent’ is ‘hateful to men’. Such contrasting feelings also applied to swords, which were instruments of order (protecting one’s self, comrades, kingdom) and chaos (destroying those of your enemy). This tension is captured by a Valkyrie in the poem Helgakviða Hjǫrvarðssonar, who knows a sword that is ‘better than all the rest’ – but it is also ‘the evil one among battle-needles’. This verse may encapsulate why swords and snakes intertwined in Viking minds: two powerful beings that were at once alluring and deadly. References Brunning, S., ‘”(Swinger of) the Serpent of Wounds”: Swords and Snakes in the Viking Mind’ in Representing Beasts in Early Medieval England and Scandinavia, ed. by Michael D. J. Bintley and Thomas J. T. Williams (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2015)

Read More

Viking Objects

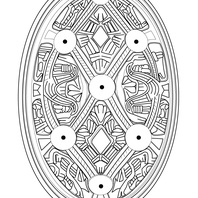

Polyhedral Weight (LIN-752A9C)

This copper-alloy weight is of a type common within the Scandinavian diaspora. This example has fourteen sides and four dots on each of the rectangular sides. These weights were adopted by the Vikings from Middle Eastern examples and appear to have become a de facto weight standard for traders. Weights are an important form of evidence for Viking Age commerce and the use of standards across the different economic systems within which Vikings were integrated. Many of the weights discovered, particularly ones in Ireland and those of Arabic type, suggest that a standardized system of weights existed in some areas. These standard weights, alongside standard values of silver, are what allowed the bullion economy of Viking occupied areas to function. A bullion economy was a barter economy that relied on the exchange of set amounts of precious metal in various forms, such as arm-rings or coins, for tradable goods, such as food or textiles. Each merchant would have brought their own set of weights and scales to a transaction to make sure that the trade was conducted fairly.

Read More

Viking Designs

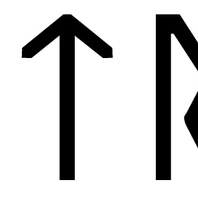

Drawing of Oval Brooch

Drawing of an oval brooch based on examples for Adwick le Street, Doncaster. Brooches were a typical part of female dress. Scandinavian brooches came in a variety of sizes and shapes which included disc, trefoil, lozenge, equal-armed, and oval shapes. The different brooch types served a variety of functions in Scandinavian female dress with oval brooches typically being used as shoulder clasps for apron-type dresses and the rest being used to secure an outer garment to an inner shift. Anglo-Saxon brooches do not match this diversity of form with large disc brooches being typical of ninth century dress styles with smaller ones becoming more popular in the later ninth and tenth centuries. However, since disc brooches were used by both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian women they are distinguished by their morphology. Scandinavian brooches were typically domed with a hollow back while Anglo-Saxon brooches were usually flat. Moreover, Anglo-Saxon brooches were worn singly without accompanying accessories.