Viking Designs

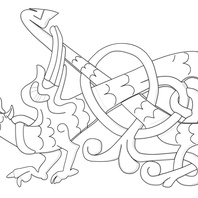

Drawing of Detail from the Southwell Lintel

The lintel above a door in Southwell Minster features the Archangel Michael fighting off a Norse-style ribbon beast. This drawing shows a detail of the ribbon beast. The lintel is probably an eleventh-century grave cover that was recarved and decorated in the twelfth century and placed into a new position.

Read More

Viking Objects

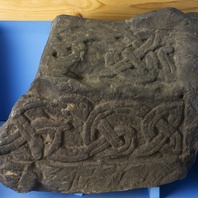

The Hickling Hogback

The Hickling hogback is a type of Anglo-Scandinavian grave cover in St Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire. It is the most southerly grave cover of this type in England. It appears to have been carved from the remains of a Roman column, hence the notch in the end of it. The stone features Scandinavian Jelling-style decoration indicating an expression of Scandinavian identity and muzzled bears on each end which are thought to be indicators of a pagan identity. However, the stone also features a large cross showing that the commissioners of the carving had a strong interest in expressing the Christian identity of the deceased. As such, this stone is designed to show that the person buried under it was a Christian Scandinavian.

Read More

Viking Objects

Whetstone (NLM-7FA566)

Whetstone fragment, possibly made of slate that looks like ‘phyllite’, where the the broken end of the hone has been sheathed in lead, which has held its parts together. This is an unusual example of the repair of a personal hone so it could be continued to be carried and used after its breakage. The hone would originally have been of a tapered bar-shaped form and was sawn to shape. Hones of this size were personal items to be carried and worn at the belt alongside the knife they sharpened. True ‘phyllite’ hones came from Telemark in Norway, and were among the first imported whetstones of the Viking Age. A range of other banded and coloured stones, many found in graves at Birka, were adapted for similar use, and their fine appearance was as important as their usefulness as sharpening stones.

Read More

Viking Objects

Repton Stone (1989-59/1165)

The Repton Stone, as it is now known, was found in a pit near the eastern window of the Church of St Wystan, Repton, Derbyshire in 1979. It was originally carved on all four faces, but recognisable detail remains only on two of them. The Repton Stone is a section of a sandstone cross shaft carved on one side with a mounted armed figure (Face A), on the other with a monstrous creature eating the heads of two people (Face B). It was broken Face A: A moustachioed armed figure on horseback with sword and shield raised in the air is carved on this face. The horse is very clearly a stallion. Incised decoration, where the design is scratched into the surface, shows that the rider was depicted wearing armour and carrying a second weapon at his waist, perhaps a seax (knife or dagger). The armour was probably intended to be mail although the carving suggests scale. The mounted man appears to be wearing a diadem, suggesting that he was of high rank. He is wearing a pleated tunic under his armour, and has cross-gartered legs. The reins of the horse are looped over his right arm. Elements of the tack are clearly visible. Face B: This face would have been on the side of the cross. The monstrous creature on this face consists of a snake-like body with the face of a human being. The serpent beast appears to be devouring the heads of the two human figures that embrace in front of it. The serpent may be a representation of the Hellmouth devouring souls. The pit the stone was found in probably dates to the eleventh century or early twelfth century. However, the cross was probably much earlier in date, being broken up close to the time it was deposited in the pit. It is probable that the cross was made before the Viking camp in 873/4 because the monastery that stood on this site before the Vikings was not refounded after the Vikings adopted Christianity. The presence of this cross at the site of a Viking camp shows that Repton was an important place before the Vikings made it their temporary abode. This may have been one reason that the Vikings chose Repton for one of their camps, although its proximity to the River Trent would also have been an important factor. The Vikings used waterways to access the interior of the country, so it is not surprising to find their winter camps beside navigable rivers.

Read More

Viking Objects

St Alkmund’s Hogback Grave Marker (1996-60-5)

A stone hogback grave marker from St Alkmund’s Church, Derby. The site of St Alkmund’s Church is thought to have been on one of the oldest Christian sites in the area. Excavations on the site have shown that the church was in existence before the ninth century and that the presence of the Great Army in the ninth century seems to have led to a period of neglect and decay, before it was restored following the reconquest of the Danelaw in the tenth century or early eleventh century. Only about half of this hogback grave cover survives. It has the typical bear at the gable end, although the carving is damaged, and an interlaced serpent design within the panels on the side. It is typical of this type of grave cover which is found throughout northern England and into Scotland. They occur in Viking-dominated areas of the country, and appear to be an Anglo-Scandinavian tradition combining elements of pre-Christian and Christian iconography.

Read More

Viking Designs

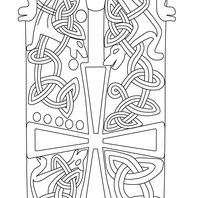

Details from the Hickling Hogback

Detail drawings showing elements of the designs on the hogback stone, a type of Anglo-Scandinavian grave cover, from St Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire.

Read More

Viking Objects

Circular Weight (LEIC-5C4051)

This circular weight has a centrally placed orange stone chip inlaid into it. The distinction of weights by embedded objects or other embellishments in various media is a widely recognised feature of some early medieval weights. Weights are an important form of evidence for Viking Age commerce and the use of standards across the different economic systems within which Vikings were integrated. Many of the weights discovered, particularly ones in Ireland and those of Arabic type, suggest that a standardized system of weights existed in some areas. These standard weights, alongside standard values of silver, are what allowed the bullion economy of Viking occupied areas to function. A bullion economy was a barter economy that relied on the exchange of set amounts of precious metal in various forms, such as arm-rings or coins, for tradable goods, such as food or textiles. Each merchant would have brought their own set of weights and scales to a transaction to make sure that the trade was conducted fairly.