Blog Post

Watling Street, the Danelaw and the East Midlands, Part 1

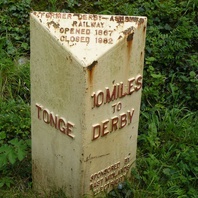

Watling Street, (c) K. Holman 2018 When Svein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, launched his invasion of England in 1013, he landed in Lincolnshire and, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, received the submission of Earl Uhtred and the Northumbrians at Gainsborough, followed by ‘all the people in Lindsey, and afterwards the people of the Five Boroughs [Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, and Stamford], and quickly after, all the raiding-army to the north of Watling Street’. This brief reference neatly highlights the geopolitical diversity of the East Midlands in the Viking period, listing the various local factions who allied themselves with Svein Forkbeard against the English king, Æthelred II. Importantly, it also suggests that Watling Street marked a clearly recognised border running through the former kingdom of Mercia, a point that is underlined by the Chronicler’s next statement that Svein ‘after he came over Watling Street […] wrought the greatest evil that any raiding-army could do’. The clear implication is that those living to the south of this old Roman road were seen as Svein’s enemies and treated accordingly. But, with the present political debates about hard and soft land borders in mind, how did Watling Street come to be seen as a political frontier running through the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia? A view along Watling Street, (c) K. Holman 2018 Watling Street – or Wætlingastræt – is the name that the Anglo-Saxons gave to the road that the Romans built to connect Dover with Wroxeter. It cut a roughly diagonal line, perhaps as much as six metres wide, running from the south-east, via London and St Albans, to the north-west of the country, crossing central England. Built in the mid-first century AD, it clearly continued to be an important route through the landscape long after the Romans had left, not least to the ‘Great Army’ of Vikings that arrived in England in 865 and defeated the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia in 874. Watling Street – as well as other Roman roads – allowed these Viking raiders to move quickly across long distances, which must have been an important factor enabling their victories across far-flung parts of Anglo-Saxon England, and bringing about the rapid collapse of the kingdoms of East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia. The road still continues to divide the East Midlands from the West Midlands, preserved along much of the A5, which runs through Northamptonshire, and then forms the county boundary between Warwickshire and Leicestershire (with an important deviation that allowed Tamworth, lying to the north of Watling Street, to be incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon zone). Map showing the line of Watling Street As well as being mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1013, Watling Street is also mentioned in the treaty terms agreed by King Alfred the Great and his recently defeated Viking rival, Guthrum, sometime before 886, at a time when the last surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex was struggling for its survival. This agreement acknowledged clear spheres of control between the English and Danish leaders, and secured Alfred’s own kingdom of Wessex from the threat of Danish armies by recognising Guthrum’s control of East Anglia. The dividing line between Alfred’s and Guthrum’s kingdoms was outlined in some detail: ‘First concerning our boundaries: up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then in a straight line to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street.’ However, there is no suggestion in this treaty that the border continued to run north and eastwards along Watling Street through the Midlands, although some historians assume that this must have been the case. Instead, it looks like Alfred and Guthrum didn’t discuss the political situation in Mercia or attempt to define any boundaries there. This isn’t surprising as, of course, Guthrum wasn’t the only Viking leader harrying the English countryside in the ninth century, and other Viking leaders weren’t bound by the treaty terms agreed with Alfred. In 893, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers to various oaths and pledges given to Alfred by Northumbrians and East Anglians, as well as the activities of ‘other raiding-armies’. By the time the treaty with Guthrum was agreed, it is also evident that some of the Viking armies had become a permanent fixture in northern and eastern England, with references to them dividing up the land and settling down. Mercia seems to have been divided into two halves, east and west, with the western part being left under the control of Ceolwulf, while the eastern part was settled. As a key communication route, Watling Street, would no doubt have functioned as a convenient dividing line to all parties in working out details of any agreement in Mercia. However, it seems that any agreement was fairly short-lived, and certainly the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records how, after his death, Alfred’s son and daughter – Edward the Elder and Æthelflæd – campaigned north of Watling Street, trying to win back control of the area from the Viking armies. A series of fortified strongholds were constructed at key points across southern England, with those at Tamworth and Towcester representing English defensive points on Watling Street. By 921, ‘all the people that was settled in the land of Mercia, both Danish and English’ are said to have ‘turned to’ Edward, although this clearly glossed over the political realities of the continued struggle for control of the East Midlands. The arrival of Norsemen from Ireland around this time complicated the political landscape further, and one of their leaders, Olaf Guthfrithson, attempted to extend his control from York into the East Midlands. Following a devastating attack on Tamworth, Olaf met with King Edmund, Edward’s son, at Leicester, and Simeon of Durham records that their agreement in 941 specified that ‘Watling Street was the boundary of each kingdom’. But when Olaf died in the following year, Edmund captured the Five Boroughs and ‘conquered Mercia’. By the 960s, Alfred’s great-grandson, Edgar, was able to stipulate that his laws should ‘be common to all the nation, whether Englishmen, Danes or Britons’. The ‘Danelaw’ had apparently been reconquered by Alfred’s West-Saxon dynasty less than a hundred years after Alfred’s and Guthrum’s treaty and absorbed into a single political nation. So why, in 1013, was the Danish king, Svein Forkbeard, able to rely on the support of what is described as the here – the raiding army – north of Watling Street, long after the ninth-century Viking armies had dispersed and settled, and northern and eastern England had apparently been integrated into the kingdom of England? Find out in part 2 of this post.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Silver Ingot

A white metal reproduction of a Viking Age silver ingot. Silver goods and coins might be melted down into ingots for ease of carrying.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Tweezers

Tweezers were an essential toilet item for the Vikings and most people would have had their own. They could be highly decorated as were many personal possessions. They would have been carried suspended from a brooch or belt.

Read More

Viking Names

Staythorpe

Staythorpe, in the Thurgarton Wapentake of Nottinghamshire, comes from the Old Norse male personal name Stari and the Old Norse element þorp ‘outlying farm, settlement’.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Lozenge Brooch

A copper alloy lozenge brooch in the Borre style based off a find in Lincolnshire. This type of brooch was common throughout the Danelaw in the Viking Age and was used as an accessory by women who wore Scandinavian dress. Scandinavian brooches came in a variety of sizes and shapes which included disc, trefoil, lozenge, equal-armed, and oval shapes. The different brooch types served a variety of functions in Scandinavian female dress with oval brooches typically being used as shoulder clasps for apron-type dresses and the rest being used to secure an outer garment to an inner shift. Anglo-Saxon brooches do not match this diversity of form with large disc brooches being typical of ninth century dress styles with smaller ones becoming more popular in the later ninth and tenth centuries. However, since disc brooches were used by both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian women they are distinguished by their morphology. Scandinavian brooches were typically domed with a hollow back while Anglo-Saxon brooches were usually flat. Moreover, Anglo-Saxon brooches were worn singly without accompanying accessories.

Read More

Viking Names

Stamford

Stamford, in the Ness Wapentake of Lincolnshire, is one of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw. The place-name comes from the Old English elements stan ‘stone’ and ford ‘ford’. The town is located near a point where the River Welland was easily fordable throughout the year. In 913 The Great Heathen Army arrived in Stamford.

Read More

Viking Names

Derby

Derby, in the Morleyston and Litchurch Hundred of Derbyshire, is the only one of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw to bear a Scandinavian name. It is also one of the few instances of a Scandinavian-named place for which we have an earlier English name. The English name is Norðworðig from the Old English elements norð ‘north’ and worðig ‘enclosure’. This is possibly related to Derby’s position, slightly north-east of Tamworth and that the enclosure’s northernness is relative to the ancient capital of Mercia. In standard reference books the name Derby is explained as Djúrabý, comprising Old Norse djúr ‘deer’ and by ‘farm, settlement’. Furthermore the compound recurs in the British Isles, and probably refers to a particular function – djúrabý ‘specialised production units that had earlier formed parts of multiple estates’. However, the first element of the name probably has a completely different derivation based on its location on the River Derwent, whose name is pre-English in origin. The form of the river-name in the Anglo-Saxon period was Deorwente. Scandinavian settlers hearing this river-name could have associated the first element deor with the familiar compound djúrabý, or indirectly adapted the Romano-British settlement name Derventio. It is certainly possible that the Romano-British name continued in use to refer to the fortified area in the Anglo-Saxon period. Mint-signatures from Derby point to the likelihood not only that Deoraby originally referred specifically to the area of the Roman fort, but also that it is a Scandinavianisation of a pre-existing name of British origin used by the Anglo-Saxons.

Read More

Viking Names

Toton

The name of Toton, in the Broxtow Wapentake of Nottinghamshire, comes from the Old Norse male personal name Tófi and the Old English element tun ‘farm, settlement’. It is thus a hybrid name, like others in the region. There are several examples in the Trent valley such as Gonalston or Rolleston. Such names are often called Grimston-hybrids, but the late Kenneth Cameron, formerly professor at the University of Nottingham, always preferred the term Toton-hybrids, since the element ‘Grim’ does not always derive from an Old Norse personal name.

Read More

Viking Names

Colston Bassett

Colston, in the Bingham Wapentake of Nottinghamshire, comes from the Old Norse male personal name Kolr and the Old English element tun ‘farm, settlement’. It is thus a hybrid name like others nearby, such as Thoroton and Aslockton. Bassett was added in the twelfth or thirteenth century from the name of an owner of the manor. Such suffixes were used to distinguish this Colston from Car Colston, some eight miles to the north of Colston Bassett.

Read More

Viking Names

Barnby Moor

Barnby, in the Bassetlaw Wapentake of Nottinghamshire, probably comes from the Old Norse elements barn ‘child’ and by ‘farm, settlement’. Its meaning, ‘children’s farm’, may indicate joint inheritance by the offspring. However, it is also possible that the first element is from the Old Norse male personal name Barni.

Read More

Viking Names

Skegby

Skegby, in the Broxtow Wapentake of Nottinghamshire, comes from the Old Norse male personal name Skeggi ‘the bearded one’ and by ‘a farmstead, a village’.