Viking Names

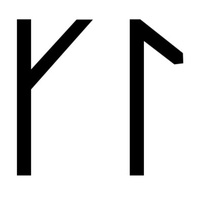

Hroald

Hróaldr was a common name throughout Viking Age Scandinavia, appearing in a few Swedish and Danish runic inscriptions. The name is used in modern Scandinavian today as Roald which was given the famous British children’s author Roald Dahl by his parents who were Norwegian immigrants to Wales. The personal name also appears as the first element in the place-name Rolleston, Nottinghamshire.

Read More

Viking Names

Gunni

Gunni is a short form of Old Norse personal names in Gunn– from Old Norse gunnr, guðr ‘battle’. The personal name is very common throughout areas of the Viking diaspora and occurs in several place-names including three in Normandy. Gunni is also found in Danish and Swedish runic inscriptions. Gunni is the first element in three Lincolnshire place-names: Gunness, Gunby, and Gunthorpe.

Read More

Viking Names

Tofi

The name Tófi is very common in the Viking Age, though mostly in Sweden and Denmark. It forms the first element of the hybrid place-name Toton, Nottinghamshire.

Read More

Viking Names

Thorgeir

The male name Þorgeirr is extremely common in the Viking world (including Ireland and Normandy) and an anglicised version appears as the first element of the village- and wapentake-name Thurgarton in Nottinghamshire.

Read More

Viking Names

Sigulf

Sigulfr is a Scandinavian male personal name from Old Norse Sig- ‘victory’ and Old Norse -ulfr ‘wolf’. The name is possibly found in a Norwegian place-name and appears once in Jämtland (modern day Sweden) in 1347. The name is recorded in Sweden as runic sikulf and in the forms Sighulf, Sigell and possibly in the much contracted form Siel in Denmark. Sigulfr is also the first element in the place-name Sileby, Leicestershire.

Read More

Viking Names

Hasland

Hasland, in the Scarsdale Hundred of Derbyshire, is an Anglo-Scandinavian compound from Old English hæsel ‘a hazel-tree’ and Old Norse lundr ‘a small wood’. Earlier forms of the place-name such as Heselunt and Heslond show influence from Old Norse hesli ‘hazel-wood’.

Read More

Viking Names

Broklaus

The postulated Old Norse male personal name Bróklauss is likely an Anglo-Scandinavian formation. It is originally a byname from the Old Norse elements Brók- ‘breeches’ and -lauss ‘less’. It is the first element in the place-name Brocklesby, Yarborough Wapentake, Lincolnshire, and in a field-name in Broughton, in Manley Wapentake, also in Lincolnshire.

Read More

Blog Post

Blazing Saddles? Saddles in the Viking Age (Part 2)

This is part 2 of a blog post on Viking Age riding equipment. You can read Part 1 HERE. Viking saddles develop from the 4th century AD, with Eurasian influences very obvious, and there’s a bit of Roman influence there too, but when you think of the great war booty deposits of the Roman Iron Age in that region, that is very much to be expected. Typically, the saddles have high pommels, and occasionally high padded cantles to create a very secure and comfortable seat, although we are still uncertain about some aspects of their construction and use. Often there are gullets and pommel horns not unlike a modern Western saddle, enhancing the comfort aspect for the long distance rider. When we consider the pacing animals in Nordic equitation, and the glorious flying tölt they execute, then this makes a lot of sense. The pace of these ponies eats the miles up with maximum comfort. You would not want to spend an entire day cross-country hacking in a flat dressage saddle as you’d be very ‘Thor’ at the end it all ( sorry). It has to be noted that it is very difficult to knock someone out of one of these saddles. Saddles have been found in burials around Scandinavia in various states of preservation, sadly none of them ultimately satisfying to the archaeological mind, but I have to say I’ve been quite taken with the reconstructions by Carlstein (2014) to fill in the gaps of Vendel (and as a result Viking) saddlery. Examples have been found at Vallstenarum, in Gotland, and also in the Valsgärde 7 burial (see Fig. 4), both Vendelic, but there is such a huge continuity of style, the chronological devil appears to be in the details. These saddles were decorated with metal mounts on both pommel and cantle (Lindgren 2017; Carlstein 2014; Arwidsson 1977). The most complete example is the Oseberg saddle, which dates between AD 800 -900 (Bonde and Christansen 1993). It is made of beechwood, and in the absence of the padding it would have had around it, stud marks are visible, which may well suggest it too would have had decoration of some kind. Likewise with the frame of a saddle found at Fishamble Street in Dublin (Kavanagh 1988). Fig. 4. Reconstruction of Valsgärde saddle, from Arwidsson 1977. Bling was commonplace on Viking equestrian equipment, making the ordinary workaday object into something very beautiful. Many of the decorative mounts which share commonalities of design may well mark out specialist workshops, sought out because they created things of power and beauty. Back for a moment to the Vendel saddles of the 7th century AD at Vallstenarum in Sweden; it is notable because of its finely worked hawk or falcon decorative mounts. These little objects, now on display in the Statens Historika Museet in Stockholm are just under 8 cm in length, very close indeed to the length (7.4 cm) of the Leicestershire piece. On their reverse side, the bird of prey mounts of the Vallstenarum saddle have dents and marks indicating that they were attached by small rivets and pins in a manner similar to our UK mystery piece. This ‘pinning’ is noted by Akhmedov (2018, 518) in his discussion on the fantastical little creatures and human features which decorated equestrian equipment during the early medieval period in northwestern Europe and Scandinavia (Akhmedov 2018, 520). If we are to go purely on the indentations and places where rivets have connected it to something, it would seem fairly plausible that this was perhaps one of a pair of very fine saddle decorations. A caveat must be emphasised again that the mount could be from clothing, jewellery, a box holding precious things – there are a host of possibilities. I think one of the areas I would want to examine would be the off-centre, very raw perforation in the piece. It appears to be from being placed on something which had stretched or altered shape slightly in use, which also may point towards saddlery. The tree of saddles are wood and the padding leathers and fibre, and these stretch with time and regular, repetitive use. It is why horsie folks tend to check their saddles on a fairly regular basis. We do not have pretty gold and copper alloy decorations anymore (more’s the pity) but if we did, and the saddle was worn, the perforation of a softish metal would warp slightly, showing how we were riding – straight or lopsided. An analysis of use-wear, and direction of ‘tug’ may provide some interesting information. Likewise with the metal itself, a quick, non-invasive analysis via pXRF would indicate the nature of the alloy. The symbolism of the creatures and the little manikin with the staring eyes no doubt have their own story to tell (Nordqvist 2013), which I would feel safer being left in the hands of Viking specialists, but for now, this little object offers a potential insight into someone’s unique tastes and preferences in decorating for power and success. Akhmedov, I. 2018. ‘Matrices from the Collection of K.I. Ol’shevskij. The North Caucasian group of Early Medieval imprinted decorations’ in Nagy, M and Szőlősi, K (eds) To make a fairy’s whistle from a briar rose” Studies presented to Eszter Istvánovits on her sixtieth birthday. Nyíregyháza: Jósa András Múzeum 505-527 Arwidsson, G. 1977. Valsgärd 7 AMAS ( Die graberfund von Valsgarde 3) Uppsala Bersu, G. and Wilson, D.M. 1966. Three Viking graves in the Isle of Man (No. 1). Society for Medieval Archaeology. Bonde, N. and Christensen, A.E., 1993. ‘Dendrochronological dating of the Viking Age ship burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, Norway’. Antiquity. 67. 256. 575-583. Carlstein, C. 2014. Krigarens säte i striden? En kvantitativ studie av beslag och ringar tillhörande den Sydskandinaviska ringsadeln, med utgångspunkt i fynden från krigsbytesofferplatsen i Finnestorp. Unpubished dissertation. Göteborgs Universitet Geake, H. 2005 Medieval Archaeology 49, Available at: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-769-1/dissemination/pdf/vol49/49_323_473_med_britain.pdf Kavanagh, R., 1988. ‘The horse in Viking Ireland’ in Bradley, J and Martin F.X (eds) Settlement and society in medieval Ireland. Boethius Press, Kilkenny. 89-121. Lindgren, S. 2017 Glimmande artefakter och vendeltida social struktur – En studie av järnålderslandskapet i Vallstena socken på östra Gotland 7th century AD. Unpublished dissertation Uppsala University Nordqvist, B., 2013. ‘Symbols of identity: A phenomenon from the migration period based on an example from Finnestorp’ in Bergerbrant, S and Sabatini, S (eds.) Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristian Kristiansen Oxford :BAR S2508. 213-221. Pedersen, A. 1996-97. ‘ Riding gear from late Viking Denmark’ Journal of Danish Archaeology .13. 133-161 Wilde, W.R., 1861. A descriptive catalogue of the antiquities of animal materials and bronze in the museum of the Royal Irish Academy. Dublin: Hodges. Dr Rena Maguire recently completed her PhD at Queen’s University Belfast. Her main research interests lie in Late Iron Age material culture studies, metals and horses.

Read More

Viking Objects

Samanid Dirham Fragment (CM.840-2002)

This is a silver dirham which was minted during the reign of the Samanid ruler Akhmad Ibn Ismail (907-14) or Nasr ibn Ahmed (914-43) in Samarkand. The dirham was a unit of weight used across North Africa, the Middle East, and Persia, with varying values which also referred to the type of coins used in the Middle East during the Viking Age. These coins were extremely prized possessions not only for their silver value but as a way of displaying ones wealth, status, and vast trade connections. Millions of Arabic Dirhams would have been imported throughout the Viking world and are mostly found in hoards. Arabic coins are especially useful for dating sites, because they carry the date when they were minted. This permits precise dating where the part of the coin with the date survives, whereas European coins can only be dated to the reign of the ruler depicted on them. In western descriptions of these coins, the Arabic dates found on the coins are usually listed in square brackets, as above, and the European equivalent is listed after it. This coin was part of a hoard of twelve coins found at Thurcaston between 1992 and 2000. The coins are Anglo-Saxon, Arabic and Viking issues, and show the diverse and wide-ranging contacts between societies at this time. The hoard was probably deposited c.923-925 CE, approximately five years after Leicester had been retaken by Mercia (c.918 CE). They indicate that a bullion economy was still operating in the Danelaw as late as the 920s. This suggests that the reconquest did not manage to institute Anglo-Saxon practices such as a monetary economy immediately.

Read More

Viking Names

Grim

The Old Norse male name Grímr is common across the Scandinavian world, including the Viking diaspora. It is very common in English place-names, though some of these might rather represent an Old English mythological name associated with Woden, and there are other possibilities. For this reason, not all the hybrid names traditionally referred to as ‘Grimston hybrids’ necessarily have an Old Norse element and it is better to refer to them as Toton-hybrids. However, where the name is compounded with an Old Norse element such as -by (as in Grimsby), it is likely that it represents the Old Norse personal name. In Old Norse, Grímr is related to the word gríma ‘mask’ and mythological texts relate that is one of the god Óðinn’s by-names, deriving from his penchant for travelling about in disguise. It is also a common element in compound personal names, such as Þorgrímr. The father of the eponymous hero of Egils saga was called Skalla-Grímr ‘Bald-Grim’.

Read More

Viking Objects

Breedon Silver Ingot (X.A236.2009.0.0)

A Viking silver ingot which could have been used as bullion in payments or trade transactions, as well as a source of metal for jewellery making. The Vikings arriving in England had a bullion economy where they paid for goods with silver that was weighed to an amount agreed between the buyer and the seller. Hacksilver and silver ingots are the most common evidence for their bullion economy. It took some time for the Scandinavian settlers to adopt a monetary economy like that of the Anglo-Saxons, and both systems were used simultaneously for a while before they fully adopted the new system. They were familiar with monetary economies but they treated coins as just another form of silver before adoption of a monetary economy.