Viking Objects

Viking York Penny (1995-17)

This silver penny was found during demolition work at St Alkmund’s Church in 1967. This type was minted at York for the rulers Sigeferth and Cnut, but this coin has no names, whether of a ruler, a moneyer or a mint. Sigeferth is recorded as being a pirate in Northumbria around 893 and seems to have assumed control after Guthfrith’s death in 895. Cnut is not attested in written sources but Scandinavian tradition places him in Northumbria around the same time. The joint Sigeferth Cnut coins and the sole issues of Cnut were minted around c. 900. This type of penny is known as Mirabilia Fecit from the Latin Cantate Dominum canticum novum, quia mirabilia fecit. Mirabilia fecit means ‘he made it marvellously’ and is the inscription on one side of the coin while the other has the inscription DNS DS REX (‘Dominus Deus rex’ = ‘the lord God almighty is king’).

Read More

Viking Names

Donisthorpe

Donisthorpe, historically belonging to the Repton and Gresley Hundred of Derbyshire, comes from the Norman male personal name Durand (Middle English genitive singular Durandes) and the Old Norse element þorp ‘outlying farm, settlement’. Place-names containing þorp are thought to be later names, or at least rather longer lived, than those containing the Old Norse element by ‘farm, settlement’ because there are more instances of post-Conquest-type elements combined with þorp than by. Donisthorpe is an example of one of these place-names. Donisthorpe is a joint parish with Oakthorpe and they were both transferred to Leicestershire in 1897. These place-names are close in proximity to Boothorpe and Osgathorpe in Leicestershire demonstrating the density of the Old Norse element þorp across the medieval and modern landscape.

Read More

Viking Names

Ashby Parva

Ashby Parva, in the Guthlaxton Hundred of Leicestershire, is an Anglo-Scandinavian hybrid from Old English æsc ‘ash-tree’ and Old Norse by ‘a farmstead, a village’. There may have also been possible influence on the first element from Old Norse eski ‘a place growing with ash-tree’ or Old English esce ‘a stand of ash-trees’. Affixes such as the Medieval Latin parva ‘small’ and Middle English litel ‘little’ were variously added to different forms of the name to avoid confusion with nearby Ashby Magna.

Read More

Viking Names

Carlton Curlieu

Carlton Curlieu, in the Gartree Hundred of Leicestershire, is a partly Scandinavianized form of Old English Ceorlenatun, from Old English ceorl (ceorlena genitive plural, Old Norse karl, genitive plural karla) ‘a freeman of the lower class, a peasant’ combined with Old English tun ‘an enclosure; a farmstead; a village; an estate’. The feudal affix Curlieu is the family name of William de Curley who held the manor in 1253.

Read More

Viking Names

Freeby

Freeby, in the Framland Hundred of Leicestershire, comes from the Old Danish male personal name Fræði (genitive singular Frætha) combined with the Old Norse element by ‘a farmstead, a village’.

Read More

Viking Names

Sysonby

Sysonby, in the Framland Hundred of Leicestershire, comes from the Old Norse male personal name Sigsteinn (Middle English genitive singular Sigsteines) and Old Norse by ‘a farmstead, a village’.

Read More

Collection

Viking Designs

In this collection you can view and download designs based on some of the objects in the Viking Objects collection. The drawings have been made by Adam Parsons of Blueaxe Reproductions. They are open-access and available to use under Creative Commons CC-BY-4.0. They are available to download and print out as jpg, pdf or eps files.

Read More

Blog Post

The Danelaw: a place or an idea?

Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. Photo by Judith Jesch. The Danelaw: a place or an idea? This question was posed by Melvyn Bragg in a recent edition of In Our Time on Radio 4. The correct answer is ‘a bit of both’. But it’s a very good question and one worth a bit more exploration. As an area, the Danelaw is often thought to have been established in the treaty made at Wedmore between King Alfred and the Viking leader Guthrum in the 880s. While only recorded in later manuscripts, it is generally accepted as a true record of what was just one of several treaties between English rulers and Viking leaders at the time. The treaty is rather specific in being between ‘King Alfred and King Guthrum and the council of all the English nation and all the people which are in East Anglia’. It defines a boundary which goes ‘up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then straight to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street’. In this way the treaty delineates the area within which the provisions of the treaty apply but does not define who is in charge there. The provisions themselves are quite basic and are to do with the relationship between Danes and English, in cases of manslaughter, the purchase of men, horses or oxen, and recruitment to either army. In all the treaty is a practical, and limited, agreement which makes no assumptions about who occupies or holds the defined territory, which is in any case quite vague about how far north it might extend. There is also no suggestion in the treaty of any difference between ‘Danish’ and ‘English’ law, in fact the treaty takes pains to assess the compensation for the manslaughter of an English or a Danish man at the same amount. The idea that there are two legal jurisdictions, in which that of the Danes, or of Danish-held territory, is distinct from its English equivalent, does not become clear in documents until the early eleventh century. In these, lagu ‘law’, an Old Norse word introduced into Old English by Archbishop Wulfstan, collocates with the ethnonym Dena to express the idea of the ‘law of the Danes’, but the term is not yet a compound as in ‘Danelaw’. For example, in Æthelred’s law code (VI) of 1008, Wulfstan distinguishes between on Ængla lage 7 on Dena lage be þam þe heora lagu sy. This might be translated as ‘in the jurisdiction of the English and in the jurisdiction of the Danes according to what their legal practice might be’ and there are several similar uses of the term around this time. What this shows is that there is an idea of a Scandinavian (or Anglo-Scandinavian, as argued by Lesley Abrams) legal province within the English kingdom. This province is presumably territorially defined, though this is not actually indicated in the legal codes themselves. An earlier code of Æthelred (III, from around 1002, known as the Wantage code), does not use the Danelaw term but does mention the Five Boroughs and makes extensive use of Scandinavian legal language in legislating for that region. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in a poetic entry for 942, makes a distinction between the Danes of the Five Boroughs (Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford) and the Norsemen who ruled north of them and from whose subjugation the Danes were freed by King Edmund. All this suggests that the Scandinavian legal province recognised in the law codes of the time reached only as far as the Humber, but that the legal distinctions between Danes and English were still important (and recognised) in the eleventh century, some 50-100 years after English rulers had conquered the Scandinavian-ruled areas during the tenth century. So, ‘Danelaw’ is not a term for the area defined in the treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. Also, as a legal concept it appears only to apply to an area south of the Humber, more specifically perhaps just the region of the Five Boroughs. However neither of these is how the term is most commonly used today. Despite its origin in the law codes of the early eleventh century, today the term is most frequently used in a more general way, without necessarily any reference to law, jurisdiction or even a well-defined area. Most commonly it is used to refer to that part of England which was, for want of a better word, ‘influenced’ by the activities of Scandinavians, whether they were the so-called ‘Great Heathen Army’ of the ninth century or peaceful settlers in the tenth. It is only after King Cnut became king of all England in the eleventh century that the distinction between ‘Danish’ and ‘English’ England becomes hard to sustain. The reign of Cnut and, briefly, his son Harthacnut brought new Scandinavian incomers to England, who often reached parts of England not otherwise thought of as falling within the ‘Danelaw’ and the overall picture is quite different. To use the term ‘Danelaw’ in this general sense is actually quite misleading. It implies that only Danes were involved in the Scandinavian impact on England, and that, whether idea or area, it is mostly about law and jurisdiction. But many scholars use the term in contexts where they are looking at the Scandinavians’ influence on settlement, culture both material and immaterial, and language, as well as their impact on church and society. Evidence for this influence and impact can be found in large parts of eastern and northern England, including regions far from the area described in the Treaty of Wedmore, or the Five Boroughs. Areas in the north-west, such as Cumbria, have plentiful evidence of Scandinavian influence in burials, metalwork, place-names, dialect, sculpture and runic inscriptions, yet there is almost no documentary evidence for how this Scandinavian influence came about. Is Cumbria part of the Danelaw? It was certainly part of the great Viking diaspora that affected much of England from the ninth to the eleventh (or even twelfth) century, yet the term ‘Danelaw’ does not seem entirely appropriate to describe that region in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Perhaps it is best to use the term ‘Scandinavian England’ (as in the title of an important collection of essays by F. T. Wainwright). Even better would be ‘Anglo-Scandinavian England’, since even the areas most heavily influenced by the Scandinavian incomers never completely lost their Anglo-Saxon inhabitants, material culture, customs or language. But although the term ‘Danelaw’ is inadequate, we should not completely forget it either. At the very least it reminds us that those supposedly lawless Vikings actually gave the English language its word for ‘law’, as still used today. References: Lesley Abrams, ‘Edward the Elder’s Danelaw’, in Edward the Elder 899-924, ed. N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 128-43. Lesley Abrams, ‘King Edgar and the men of the Danelaw’, in Edgar, King of the English 959-975, ed. Donald Scragg. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008, pp. 171-91. Katherine Holman, ‘Defining the Danelaw’, in Vikings and the Danelaw, ed. James Graham-Campbell et al. Oxford: Oxbow, 2001, pp. 1-11. Sara M. Pons-Sanz, Norse-Derived Vocabulary in Late Old English Texts, Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2007, pp. 70-72. Simon Trafford, ‘The Alfred-Guthrum treaty’, in Cultures in Contact. Scandinavian settlement in England in the ninth and tenth centuries, ed. Dawn M. Hadley and Julian D. Richards. Turnhout: Brepols, 2000, pp. 43-64. F. T. Wainwright, Scandinavian England, London: Phillimore, 1975. Dorothy Whitelock, English Historical Documents I. c. 500-1042. London: Routledge, 1996 [2nd ed.]. Early English Laws http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/

Read More

Blog Post

What Does the Word ‘Viking’ Really Mean?

Late Viking Age Swedish rune-stone commemorating a man called Víkingr. Swedish National Heritage Board, Photo Bengt A. Lundberg, CC BY Judith Jesch, University of Nottingham We all know about the Vikings. Those hairy warriors from Scandinavia who raided and pillaged, and slashed and burned their way across Europe, leaving behind fear and destruction, but also their genes, and some good stories about Thor and Odin. The stereotypes about Vikings can partly be blamed on Hollywood, or the History Channel. But there is also a stereotype hidden in the word “Viking”. Respectable books and websites will confidently tell you that the Old Norse word “Viking” means “pirate” or “raider”, but is this the case? What does the word really mean, and how should we use it? There are actually two, or even three, different words that such explanations could refer to. “Viking” in present-day English can be used as a noun (“a Viking”) or an adjective (“a Viking raid”). Ultimately, it derives from a word in Old Norse, but not directly. The English word “Viking” was revived in the 19th century (an early adopter was Sir Walter Scott) and borrowed from the Scandinavian languages of that time. In Old Norse, there are two words, both nouns: a víkingr is a person, while víking is an activity. Although the English word is ultimately linked to the Old Norse words, they should not be assumed to have the same meanings. Víkingr and Víking The etymology of víkingr and víking is hotly debated by scholars, but needn’t detain us because etymology only tells us what the word originally meant when coined, and not necessarily how it was used or what it means now. We don’t know what víkingr and víking meant before the Viking Age (roughly 750-1100AD), but in that period there is evidence of its use by Scandinavians speaking Old Norse. Vikings came from a world of good stories. Shutterstock The laconic but contemporary evidence of runic inscriptions and skaldic verse (Viking Age praise poetry) provides some clues. A víkingr was someone who went on expeditions, usually abroad, usually by sea, and usually in a group with other víkingar (the plural). Víkingr did not imply any particular ethnicity and it was a fairly neutral term, which could be used of one’s own group or another group. The activity of víking is not specified further, either. It could certainly include raiding, but was not restricted to that. A pejorative meaning of the word began to develop in the Viking Age, but is clearest in the medieval Icelandic sagas, written two or three centuries later – in the 1300s and 1400s. In them, víkingar were generally ill-intentioned, piratical predators, in the waters around Scandinavia, the Baltic and the British Isles, who needed to be suppressed by Scandinavian kings and other saga heroes. The Icelandic sagas went on to have an enormous influence on our perceptions of what came to be called the Viking Age, and “Viking” in present-day English is influenced by this pejorative and restricted meaning. How to use it The debate between those who would see the Vikings primarily as predatory warriors and those who draw attention to their more constructive activities in exploration, trade and settlement, then, largely boils down to how we understand and use the word Viking. Restricting it to those who raided and pillaged outside Scandinavia merely perpetuates the pejorative meaning and marks out the Scandinavians as uniquely violent in what was in fact a universally violent world. A more inclusive meaning acknowledges that raiding and pillaging were just one aspect of the Viking Age, with the mobile Vikings central to the expansive, complex and multicultural activities of the time. In the academic world, “Viking” is used for people of Scandinavian origin or with Scandinavian connections who were active in trading and settlement as well as piracy and raiding, both within and outside Scandinavia in the period 750-1100. The Viking Age was a large and complex phenomenon which went far beyond the purely military, and also absorbed people who were not originally of Scandinavian ethnicity. As a result, the English word has usefully expanded and developed to give a name to this phenomenon and its Age, and that is how we should use it, without regard either to its etymology, or to its narrower meanings in the distant past. Judith Jesch, Professor of Viking Studies, University of Nottingham This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read More

Viking Designs

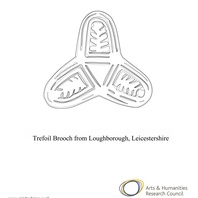

Drawing of a Trefoil Brooch

A drwaing of a copper alloy trefoil brooch of a type that would have been common in the Danelaw. Trefoil brooches were characteristically Scandinavian women’s wear. However, many examples found in the East Midlands were probably made in the Danelaw, and may have been copies of Scandinavian styles, instead of being imported from Scandinavia. Scandinavian brooches came in a variety of sizes and shapes which included disc, trefoil, lozenge, equal-armed, and oval shapes. The different brooch types served a variety of functions in Scandinavian female dress with oval brooches typically being used as shoulder clasps for apron-type dresses and the rest being used to secure an outer garment to an inner shift. Anglo-Saxon brooches do not match this diversity of form with large disc brooches being typical of ninth century dress styles with smaller ones becoming more popular in the later ninth and tenth centuries. However, since disc brooches were used by both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian women they are distinguished by their morphology. Scandinavian brooches were typically domed with a hollow back while Anglo-Saxon brooches were usually flat. Moreover, Anglo-Saxon brooches were worn singly without accompanying accessories.

Read More

Viking Designs

Drawing of a Lozenge Brooch

Drawing of a copper alloy lozenge brooch in the Borre style. This type of brooch was common throughout the Danelaw in the Viking Age and was used as an accessory by women who wore Scandinavian dress. Scandinavian brooches came in a variety of sizes and shapes which included disc, trefoil, lozenge, equal-armed, and oval shapes. The different brooch types served a variety of functions in Scandinavian female dress with oval brooches typically being used as shoulder clasps for apron-type dresses and the rest being used to secure an outer garment to an inner shift. Anglo-Saxon brooches do not match this diversity of form with large disc brooches being typical of ninth century dress styles with smaller ones becoming more popular in the later ninth and tenth centuries. However, since disc brooches were used by both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian women they are distinguished by their morphology. Scandinavian brooches were typically domed with a hollow back while Anglo-Saxon brooches were usually flat. Moreover, Anglo-Saxon brooches were worn singly without accompanying accessories.