Viking Designs

Drawing of a Viking Sword

This is a drawing of a Viking Age sword which was found in Grave 511 at Repton where the invading Viking Great Army had their winter camp in 873/4. When it was found, the sword had traces of a wooden scabbard attached to the rusted blade. Analysis showed that the scabbard was lined with fleece and covered in leather. The grip was wooden and covered in a woollen textile.

Read More

Viking Objects

Spindle-Whorl (LEIC-8D89EA)

A small, plain, undecorated lead-alloy spindle-whorl. Fibres were spun into thread using a drop-spindle of which the whorls were made of bone, ceramic, lead or stone and acted as flywheels during spinning.

Read More

Viking Names

Lowesby

Lowesby, in the East Goscote Hundred of Leicestershire, is a difficult name. The first element possibly comes from the Old Norse male byname Lauss/Lausi ‘loose-living’. Alternatively it has been suggested that the first element could be derived from the postulated Old Norse element lausa ‘a slope’ which is found in Scandinavian place-names in the forms -lösa/-löse; however, this element was no longer used for place-naming by the time of Scandinavian settlement in England. The second element is Old Norse by ‘a farmstead, a village’.

Read More

Collection

Viking Objects

In this collection you will find links to images of a wide range of objects associated with the Viking Age in the East Midlands (and a few from nearby counties). The objects are from archaeological excavations, or from chance finds. More recently many finds have been made by metal detectorists. We reproduce images of the original objects with the permission of the museums that own them, or of the Portable Antiquities Scheme which records finds by members of the public. We are also delighted to provide photographs of reproductions of the original objects made by Adam Parsons of Blueaxe Reproductions. The reproductions are intended to give you an idea of what such items looked like when they were new, rather different from the often very sorry state they are in now.

Read More

Blog Post

Watling Street, the Danelaw and the East Midlands, part 2

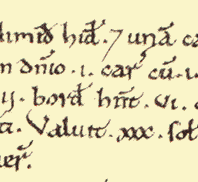

If you’ve not read the first part of this blog post, you can find it HERE. Why, in 1013, was the Danish king, Svein Forkbeard, able to rely on the support of what is described as the here – the raiding army – north of Watling Street, long after the ninth-century Viking armies had dispersed and settled, and northern and eastern England had apparently been integrated into the kingdom of England? It seems that the reality on the ground was rather more complex than Alfred’s successors would have us believe. For example, Edward the Elder issued a law code which clearly distinguishes between the rules on compensation ‘herein’ (in his own kingdom) and in the north and the east, the latter of which were instead determined by ‘the provisions of the treaties’ (in the plural). This clearly reflects the fragmented political landscape within these areas, at least before Edward’s campaign of 917. Edgar – while proclaiming his rule over a ‘united’ England – also allowed his Danish subjects considerable legal freedoms: ‘there should be among the Danes such good laws as they best decide on’. It is interesting to note that the first reference to distinctively Danish laws operating in England is found in a legal code issued by Archbishop Wulfstan of York in 1008, just a few years before Svein landed in Lincolnshire. In this code, the legal process for a man defending himself against charges of plotting against the king (at this time, Æthelred II) is said to be different ‘for those under Danish law’. Æthelred II also issued a separate legal code for the Five Boroughs of Nottingham, Leicester, Lincoln, Stamford, and Derby a little earlier, around 997. Although the areas covered by this document were considered to be part of England and under the rule of the English king, much of this law, known as the Wantage Code, aimed to extend English legal practice into the Five Boroughs. This suggests that legally, at least, important differences remained between ‘England’ and the ‘Danelaw’, which are underplayed in sources associated with the royal court of Wessex. Map showing the distribution of Scandinavian place-names and the line of Watling Street (from A. H. Smith (1956) English Place-Name Elements. Nottingham: English Place-Name Society) The place-name map bears perhaps the clearest witness to the importance of Watling Street as a dividing line between English and Scandinavian zones, showing how very few settlements with Scandinavian place-names can be found south of its line. This seems to suggest that – whatever the number of Scandinavian settlers – at the time when most of these names were given, Watling Street must have operated as some kind of border, whether that was formally established through treaties or informally observed. This is perhaps not surprising, given that there is plenty of evidence for roads being used to delimit estate and parish boundaries in the Anglo-Saxon period. One of the difficulties in using place-name evidence to understand Viking settlement is that much of the evidence for Scandinavian place-names (and indeed for place-names in general) is first recorded in Domesday Book, William the Conqueror’s record of the land-ownership, taxable values, and population, that was assembled in 1086. This makes it difficult to know exactly when the names were given, and they therefore can’t specifically be linked to the period after the conquest of Mercia in the ninth century and before the re-conquest of the Danelaw. But what we can say is that the place-names certainly suggest that the language of the people living to the north of the line of Watling Street was heavily influenced by ‘the Danish tongue’ in the period before the late eleventh century when Domesday Book was compiled and, on the basis of Svein Forkbeard’s campaign in 1013, it seems likely that this division was already clear at the beginning of that century. It is nevertheless important to remember that, even in the areas lying to the north of Watling Street, between a half and two-thirds of place-names are English. The communities that were established in the ‘Danelaw’ can’t be easily defined as ‘Danish’ or ‘English’ or even ‘Anglo-Scandinavian’ – common sense suggests that there must have been considerable local variation, with there likely to be some pockets of heavily-Scandinavianised areas and others that were less affected. Domesday entry for Blaby, Leicestershire. Place-names ending in –by are usually Scandinavian in origin. This estate’s population consisted of four villagers, four smallholders, one slave, and twenty-eight freemen. Available at: http://opendomesday.org (c) Professor John Palmer and George Slater, CC BY-SA 3.0 Domesday Book also reveals another clear difference in communities lying to the north of Watling Street in the late eleventh century: the proportion of people described as ‘freemen’ or ‘sokemen’ –essentially free peasants – as opposed to unfree cottars, bordars, and villeins. The Midlands counties of Warwickshire, Leicestershire and Northamptonshire formed a single administrative ‘circuit’ used by the Domesday commissioners, but while there are very few freemen recorded living on estates in Warwickshire, to the south of Watling Street, the numbers jump dramatically as soon as Watling Street is crossed, with freemen forming an important element in Leicestershire’s recorded population. In Northamptonshire, which is bisected by Watling Street, the same increase in the free population can be seen in the Domesday entries for estates lying to the north of Watling Street. An earlier generation of scholars, led by Sir Frank Stenton, saw the greater number of freemen in districts that had been affected by Scandinavian settlement as the descendants of huge Viking armies, who had hung up their axes and settled down to farm in the English countryside in the ninth century. Although this has long been rejected as too simplistic by historians, the distribution of these free peasants certainly suggests important social and legal conditions operated north of Watling Street, which is also hinted at in the earlier references to specifically Danish laws in northern and eastern England. As such, this evidence illustrates how Watling Street continued to mark a dividing line at the end of the eleventh century. Politically, legally, socially and linguistically, the East Midlands occupied a frontier zone, the importance of which continued to resonate through the Norman period. A view up Watling Street, (c) K. Holman 2018 Useful sources: John Baker and Stuart Brookes (2013) Beyond the Burghal Hidage: Anglo-Saxon Civil Defence in the Viking Age. Leiden: Brill. Gillian Fellows-Jensen (1978) Scandinavian Settlement Names in the East Midlands. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag. David Hill (1981) Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell. Katherine Holman (2001) ‘Defining the Danelaw’ in James Graham-Campbell et al. (eds) Vikings and the Danelaw. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 1-11. Anna Powell-Smith and J. J. N. Palmer: Open Domesday. Available online: http://opendomesday.org Pauline Stafford (1985) The East Midlands in the Early Middle Ages. Leicester: Leicester University Press. Michael Swanton (transl. and ed.) (1996) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: J. M. Dent. University of London – Institute of Historical Research / Kings College London (2018) Early English Laws. Available online: http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/ Dorothy Whitelock (ed.) (1955) English Historical Documents c. 500-1042. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

Read More

Blog Post

The Vikings in Lincoln

by Dr Erik Grigg, Learning Officer, The Collection, Lincoln The Viking Age display at The Collection, Lincoln, (c) Erik Grigg The Collection in Lincoln has a fascinating Viking display, some of which were found nearby as it is located in the heart of an important Viking trading settlement. Even the local street names indicate Scandinavian origin and demonstrate the enduring influence of the Scandinavian settlers on the area: on one side of the museum is Danesgate which means ‘Danish Street’ (gata being the Old Norse for street). The use of Old Norse gata persists in other street names around The Collection: Flaxengate, meaning the street where people were turning flax into linen to make clothes, lies immediately to the west, while Michaelgate and Hungate are only a short walk away. ‘Gate’ has become the local word for ‘street’ thanks to the Scandinavian settlers in the Viking Age. Thorfast the comb maker at The Collection, Lincoln. (c) Erik Grigg The Vikings first turned up in the area in the 870s and the Great Heathen Army made camp at nearby Torksey. The museum has a small case of finds from the recent excavations there including pieces of gold and silver hacked into convenient bits to use as treasure or currency. Viking Age artefacts on display at The Collection, Lincoln. (c) Erik Grigg After they established control, the Vikings soon settled down and turned the old Roman city of Lincoln into a vibrant trading borough. Coins and a coin die used to make them are on display in the museum as Lincoln was an important mint. The Vikings kept themselves clean and tidy and the museum has the reconstruction of a Viking comb-maker’s workshop. The finest piece on display is an eleventh or twelfth century Urnes mount, a sumptuous piece of Viking metalwork with the typical motif of intertwined dragons. Carved grave covers, a sword, axe heads and bone ice skates are also found in The Collection as well as a recently discovered rare gold Thor’s Hammer pendant. Dr Grigg has written more about the Viking Borough of Lincoln on the Visit Lincoln website.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Belt

A vegetable-tanned leather belt with a decorated copper alloy belt buckle. The buckle has a ring and dot pattern and is based on one found in Grave 511 at Repton, Derbyshire.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Trefoil Mount

A reproduction of copper alloy and gilded Carolingian mount with niello inlay found in Leicestershire. The mount has holes drilled through it for affixing to a surface, possibly a book, or perhaps to repurpose it as a pendant. These would have most likely been brought over by Vikings who had raided or traded on the European continent.

Read More

Viking Names

Langlif

In Scandinavia, the female name Langlíf is first recorded from the middle of the twelfth century. It is suggested that it occurs in scattered (and often late-recorded) place-names in England, in North Yorkshire and in Cumberland. Its occurrence in a minor name Leevingrey Furlong in Flintham, Bingham Wapentake, Nottinghamshire, has been disputed. The name also occurs in twelfth- and thirteenth-century documents from Norfolk. The name means ‘long life’ and may originally have been a by-name.

Read More

Viking Talks

Holme from Home? East Midland Place-Names and the Story of Viking Settlement

What can place-names tell us about Vikings in the East Midlands? Dr Rebecca Gregory Wednesday 20 December 2017

Read More

Viking Names

Beesby

Beesby, in the Bradley Haverstoe Wapentake of Lincolnshire, comes from a male personal name Besi and the Old Norse element by ‘a farmstead, a village’. The name Besi, which is recorded for Lincolnshire in Domesday Book, seems to be a Danelaw version of a Scandinavian name recorded in Old Danish as Bøsi. Today the name survives only in Beesby Farm and Beesby Hall, but remains of a deserted medieval village can be seen.