Viking Objects

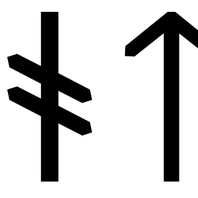

Sword Hilt or Top Guard (DENO-87124F)

A copper-alloy hilt or top guard from an early medieval, possibly Viking, sword or dagger.

Read More

Blog Post

Winter Camps in the East Midlands: Location and Layout

Our knowledge of the Viking Great Army’s movments during its campaigns in England is provided by entries in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a compilation of annalistic entries that describe events in a particular year. Despite some drawbacks to using the chronicle as a source, it does provide a roadmap for where the Vikings stopped for the winter. In fact, these were termed wintersetl by the compilers of the chronicle otherwise known as winter camps. Two of the winter camps mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are under current investigation, Repton and Torksey. © P L Chadwick, via Geograph, CC BY-SA 2.0 Both winter camps are located along a river which would have provided the Viking inhabitants with vital transportation links required in most raiding or trading activities. It would also seem likely that the waterways were selected in order to provide a natural defensive element to the settlement, usually alongside another natural feature such as a raised promontory or a marsh, or an easy means of escape if the settlement was overwhelmed. In addition, the winter camps seem to be placed in relation to recently captured territory which makes sense for force out on campaign. Viking invaders took Repton and immediately constructed a D-shaped wall using the pre-existing church as a gatehouse. The remnants of this wall were discovered in the 1970s and 1980s in the form of a V-shaped ditch, calculated to have been about 8m wide and 4m deep, cutting through the earlier Anglo-Saxon monastic burials (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 57, 59; Jarman 2018a, 29). The 1979 excavations revealed four successive ditches; the V-shaped ditch with a flat narrow bottom was the earliest and was backfilled shortly after being dug (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 58). The ditches have been dated to between the Group 2 Middle Anglo-Saxon and Group 3 Post-Viking burials, which fits with late ninth-century ‘Great Army’ occupation (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 59). A Viking sword found at Repton, Derbyshire. (c) Derby Museums 2019 Unlike Repton, in Torksey Vikings only utilized natural defences, such as the river Trent and the wet marshy ground, which turned the settlement into an island (Hadley and Richards 2016, 32; Raffield 2016, 313). Despite not having any walls or ditches, it is likely that the ‘Great Army’ would have found the water and marsh defence sufficient in light of their recent peace with Mercia (Raffield 2016, 323). A quarter of an imitation Carolingian gold solidus found near Torksey, Lincolnshire. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge In terms of buildings there is a general lack of evidence for permanent structures at both Torksey and Repton. It is unclear whether this is due to poor preservation, need for more archaeological investigation, or that they truly did not exist. The use of Repton, Torksey, and the other wintersetl as army bases during campaigning probably explains the lack of permanent dwellings and workshops from their foundation but does not explain why none were built throughout the rest of their occupation when the army left. The lack of urban planning and systems of streets and plots likely has to do with either a lack of refinement in terms of the methodology and ideas behind settlement foundation which requires more experience over time, the motivations and needs surrounding the foundation of a settlement, or even a combination of both. As mentioned above, the wintersetl in England were created, primarily, to house a military force on campaign, which moved on very quickly after the settlement was established. Therefore, it would not make sense to spend time and resources developing a systematic layout nor to begin the time-consuming process of building permanent structures. References: Biddle, Martin, and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle. 2001. ‘Repton and the “Great Heathen Army”, 873–4’. In Vikings and the Danelaw: Select Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress, edited by James Graham-Campbell, Richard Hall, Judith Jesch, and David Parsons, 45–96. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Hadley, Dawn, and Julian Richards. 2016. ‘The Viking Winter Camp and Anglo-Scandinavian Town at Torksey, Lincolnshire – the Landscape Context’. The Antiquaries Journal, no. 96: 23–67. Raffield, Ben. 2016. ‘Bands of Brothers: A Re-Appraisal of the Viking Great Army and Its Implications for the Scandinavian Colonization of England’. Early Medieval Europe 24 (3): 308–37.

Read More

Viking Objects

Imitation Carolingian Gold Solidus (CM.521-1998)

This cut-quarter of an imitation gold solidus is one of 80 known imitations as opposed to 15 official solidi and is a copy of coins issued by Louis the Pious (778-840 CE). It was probably made somewhere in Frisia on the north-west coast of what is now the Netherlands. The importance of this carefully divided quarter-coin is as evidence for the acceptance of solidi on its actual monetary value rather than as mere bullion in the 9th century; if it were hack-gold it would not have been cut so meticulously. The Vikings would have obtained real and imitation Carolingian coins through their raiding and trading activities in the Frankish Empire.

Read More

Viking Objects

Blue Glass Bead (2001/59-sf174)

This Viking Age gadrooned or Melon type dark blue glass bead was found in the Magistrates Court excavation in Derby, Derbyshire. Glass beads were a coveted item for making jewellery with some being imported from as far away as the Middle East. They were manufactured by specialised artisans who would heat various coloured glass rods over a furnace and melt the glass onto a metal stick to form different shaped beads.

Read More

Viking Objects

Gilded Mount (1989-59/7591)

A gilded copper-alloy mount with approximately eight projecting pierced lugs. The mount was found in three pieces and is incomplete. It may originally have been domed, but most of the dome is missing. It has been suggested that it was a shield boss.

Read More

Viking Names

Smisby

The first element of Smisby, in the Repton and Gresley Hundred of Derbyshire, is either Old Norse smiðr ‘smith’ or it Old English cognate smið, the second element of the place-name is Old Norse by ‘a farmstead, a village’.

Read More

Viking Names

Saxi

Saxi was originally a byname derived from Old Norse noun sax ‘short, one-edged sword’, but possibly in some instances derived from an ethnonym from the name of the Saxons. An original East Scandinavian name, it is fairly common in Sweden and very common in Denmark. The name is rare in Iceland, although it is borne by one individual in the settlement period (c. 870-930). Although common in Eastern Norway, there is only a single instance of the byname Sax is recorded in West Scandinavia in the tenth century. Saxi is found in several place-names in Normandy. It is well-attested in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire although some forms may represent the Continental Germanic male personal name Saxo. Occasionally it is difficult to determine whether the first element in place-names such as Saxby All Saints, Lincolnshire and Saxby, Leicestershire is Saxi or the Scandinavian genitive plural form of an ethnonym: Old English S(e)axe, Old Norse Saxar ‘Saxons’.

Read More

Viking Objects

Trefoil brooch (LCNCC : 2011.99)

A trefoil brooch with Borre/Jellinge-style cast ornament belonging to Peterson’s type 109. The brooch is most probably cast of copper alloy with traces of gilding on its upper surface and white metal plating on the reverse. While of Scandinavian design, many examples found in the East Midlands were probably made in the Danelaw, and may have been copies of Scandinavian styles, instead of being imported from Scandinavia. For more information on Scandinavian jewellery in England check out our blog: Brooches, Pendants and Pins: Scandinavian Dress Accessories in England.

Read More

Viking Names

Fot

The Old Norse male personal name Fótr is the name of a fairly prolific Swedish rune-carver and is found elsewhere in Scandinavia. In England, the name occurs in several place-names in Lincolnshire (Fotherby, Fosdyke and Foston), Foston, Leicestershire, and possibly in another Foston in Derbyshire. In Fotherby, the place-name preserves the original Old Norse genitive singular ending (ie. as in Fótar). Such clear indications of Old Norse grammar survive relatively rarely in modern forms of place-names. Originally, Fótr was a by-name, meaning ‘foot’.

Read More

Viking Names

Welby

Welby, in the Framland Hundred of Leicestershire, is a Scandinavian compound from the Old Norse male personal name Āli and the Old Norse element by ‘a farmstead, a village’.

Read More

Blog Post

Anglo-Viking Coinage and other currency used by Scandinavians in Leicestershire

Part of the Thurcaston Hoard. LEIC-C6D945. (c) Leicestershire County Council CC BY-SA 4.0 Working in a county that was part of the Danelaw and which had already revealed the small, but fabulously important Thurcaston hoard, found back in the 1990s (LEIC-C6D945), I was a little disappointed that in 13 years as a Finds Liaison Officer, I had only recorded one ‘Anglo-Viking’ coin. This was a ‘Cunnetti’ issue (895-902) of York, found in 2009 in Rearsby Parish (LEIC-B230B). Everything changed in late in 2015 when I was shown a St Edmund memorial penny. These were minted in East Anglia by its Scandinavian rulers c. 895-910 AD. The coins feature the often blundered inscription ‘SC EDMUND’, a dedication to the saint who was, ironically, martyred by ‘Vikings’. I told the finder how rare his coin was and that he had made my year (see LEIC-19C0DA ). St Edmund memorial penny LEIC-19C0DA (c) Leicestershire County Council, CC BY 2.0 However, it seems that these coins are like buses and within weeks I was shown another (LEIC-B7F405). By April 2016 we had the hat trick, with a third being found in the same district as the first, all in North Leicestershire ( LEIC-4FC58C). A further two examples of this coin had been found prior to the inception of the Portable Antiquities Scheme. The first and the only ‘Anglo-Viking’ coin recorded for Leicestershire on the Early Medieval Corpus (EMC – managed by the Fitzwilliam Museum who also care for the Thurcaston hoard) was found near Wymeswold in 1987 (EMC 1987: 118). The only one found in the county so far by excavation turned up during the major ‘Shires’ excavation in Leicester city centre in 1988 (A39.1988). This alone is a very important find. As an ‘Anglo- Viking’ coin lost in an urban environment, it suggests that Scandinavian traders were present or, at least, that a Scandinavian lost a coin they were hoping to use as currency there. Distribution of St Edmund memorial pennies on PAS (Cumbria example not mapped) (c) Portable Antiquities Scheme The St Edmund coins are very interesting for a number of reasons: firstly, they are not ‘legal’ tender in England, so must have been circulating amongst Scandinavian settlers. Because of this their distribution may tell us something about the locations of such settlers and also which areas were Scandinavian enough to be producing these coins. We don’t yet know for certain where these coins were minted. The majority were lost (unsurprisingly) within East Anglia, so judging by their find spots, were minted in Bury St Edmunds (also named after the saint). There are also examples now turning up in the East Midlands and the south east. The numismatist Dr. Mark Blackburn thought that some were also minted in the East Midlands, as the coins vary slightly in design. Given their distribution Leicester, Derby or Nottingham are possibilities. Nationally the PAS has recorded 37 (as of Sept 2018) and EMC has 95 (end 2017). Most were single finds from within the Danelaw, with the most northerly outlier being one in a hoard in Cumbria, and a few were found just outside the Danelaw in Oxfordshire and Staffordshire. In addition to this ‘Anglo-Viking’ coinage, other forms of currency were circulating. The Scandinavians practised what we call a ‘mixed’ or ‘bullion’ economy where coins were valued for their weight in silver as well as their face value and ‘hacksilver’- cut up artefacts or chunks of bullion were also used as currency by weight. This is why the Thurcaston hoard is important as it contains Anglo-Saxon, ‘Viking’ York and Arabic coin issues. The latter two were not legal currency, so could have only circulated as ‘bullion’. The hoard dates to 923-5 so it’s also good evidence for a mixed economy still being used by the local population at a time when the Danelaw was supposedly back under Anglo-Saxon control. ‘Viking’ silver ingot from Breedon on the Hill, Leics. DENO-CE6103. (c) Derby Museums Trust, CC BY-SA 4.0 In Leicestershire we have a few examples of this economy, most notably two ‘cigar’ shaped silver ingots which were found near Breedon on the Hill (DENO-34FB88 DENO-CE6103) and which featured in the Danelaw Saga exhibition. Nationally the PAS has recorded 163 of these ingots (136 are silver) with the largest concentrations coming from Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Yorkshire and Cumbria. We have evidence for other foreign coinage probably used as bullion. We have a silver Denier of Charles the Bald, Carolingian King of the West Franks, c.840-877, from Grimston, Melton (LEIC-9F7227). Only 8 of these have been recorded by the PAS nationally and they are thought to have circulated in fairly large numbers in eastern England in 9th and 10th century as a result of the Scandinavian presence. Even rarer is a copper alloy coin of Umayyad Syria, probably minted in Damascus and dating to the 8th century. This was found in a garden in Loughborough (LEIC-94D4D2). It’s just possible that such a coin was lost by a passing Scandinavian. We also have a rare example of ‘pecking’ -a practice of testing the purity of silver by inserting a knife blade into a coins surface. A penny of Aethelred II from Syston (LEIC-01EB53) has been pecked all over both surfaces, suggesting it went through several ’Viking’ hands who wanted to check for themselves that the coin was indeed pure silver. This currency, in its many forms, adds an important layer of evidence in a county that was in the Danelaw, but which has not yet yielded too much solid evidence for Scandinavian settlers. They add much weight to the counties few artefacts and many place-names that reflect an Anglo-Scandinavian character, but whose reliability as evidence for settlers is hotly debated. These issues were only used in Leicestershire by people who accepted them, either for their bullion value or because they were Scandinavian issues. So unless the illegal use of non-English currency was rife in the East Midlands, this currency points to a Scandinavian population. For more information on Anglo-Viking coins see: www.finds.org.uk www.emc.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk Blackburn, M.A.S. Viking coinage and currency in the British Isles, Spink 2011.