Blog Post

Viking Board Games

A reproduction of a queen for chess found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides. Jarl Rögnvaldr Kali Kolsson of Orkney composed a poem describing his nine skills in the first half of the twelfth century. These were all the skills that a member of the aristocracy in medieval Orkney and Scandinavia would have been expected to know, to be considered cultured and socially adept. Among these skills, he included board games (Old Norse tafl). It is possible that he meant chess, because chess was becoming fashionable in the courts of Europe at this time. However, Rögnvaldr could have been referring to any number of board games: Old Norse tafl refers to board games in general, rather than to one specific one. It is related to the Latin word tabula and the modern English word ‘table’. In its most general sense it refers to a flat surface, hence the board of a board game. The Old Norse word tafl is occasionally compounded with other words to specify more closely which game is meant; for example, Old Norse skáktafl means chess. Rögnvaldr lived shortly after the end of the Viking Age, but it is highly likely that the Vikings considered knowledge of these games to be an important part of a man’s social skills, as is suggested by episodes where they are depicted playing board games in the sagas, and the cultural context in which board games were played as recreation remained substantially the same from the Viking Age into the medieval period. Hnefatafl (often called ‘King’s Table’ in English) is the board game most commonly associated with the Viking Age by modern people. It can be traced back to games played in Imperial Rome from at least the first century AD under the name Ludus latrunculorum (the game of the little thieves). These games were made popular throughout Europe under the Roman Empire. They were only replaced when chess arrived in Europe from India. Hnefatafl is an asymmetric game where the defender has to try to move their king off the board while the attacker has to capture the king. Moves are made orthogonally in the same manner as a rook in chess. There are many variants of this game, using different sized grids but all have an odd number of rows so that the king may be placed in the central square. There are no detailed descriptions in Scandinavian sources that permit reconstruction of the rules. Instead the rules used now have been developed from the rules for Tablut which Carl Linnaeus wrote down in Latin in 1732. Linnaeus’ description of the game was based on his observations of how it was played among the Sámi. It is fortunate that he chose to visit the Sámi when he did, because Tablut was becoming less popular at that time; the younger people preferred card games to board games. There are gaps in the rules that Linnaeus recorded, and modern rules have been adapted to fill those gaps, and to balance the game. This has resulted in a number of variants of hnefatafl in use today. A reproduction of the Coppergate game board featuring reproduction gaming pieces Hnefatafl is attested in written sources that are supported by archaeological evidence. Ragnars saga loðbrókar mentions that Sigurðr and Hvítserkr played it, and in Morkinskinna, one of the histories of the Norwegian kings, Sigurðr Jerusalem-farer, king of Norway from 1103-1130, boasts how much stronger he is than other men, but his brother Eysteinn immediately puts him down by saying “Yes, but I’m better at hnefatafl than you!” Gull-Þóris saga mentions that two women played hnefatafl, so it was obviously socially acceptable for women to play too. Of course, while hnefatafl was a pastime, it did not always end well. Þorbjörn Hook was playing halatafl, a variant of hnefatafl that used pieces with pegs in the base that could then be inserted into holes in the board, thus making it a perfect travel game. His stepmother thought this was not a good use of his time, so she grabbed one of the pieces and threw it in his face, gouging his eye out in the process so that it hung down on his cheek. There is ample physical evidence for these games. Game boards of a type that Rögnvaldr would have known have been found in Viking Age boat burials like the Gokstad ship (c. 900) where a double-sided board was found. On one side it has a grid that may have been for hnefatafl while on the other is a grid for Nine Men’s Morris, another ancient game that was probably popularised throughout Europe under the Roman Empire. A fifteen by fifteen gridded board was found in the Coppergate excavations in Viking Age York, pointing to a variant of hnefatafl being played there. The Ballinderry gaming board with its drilled peg holes may be a board for a halatafl variant. The literary evidence also suggests that the defender’s pieces were usually red, while the attackers were white, although archaeological finds suggest a broader range of colours. Dozens of playing pieces from Viking board games have been found on archaeological sites, including the Viking camps at Repton and Torksey in England, where invading Vikings presumably whiled away their time playing these board games. Some of these were on display in the Danelaw Saga exhibition at the University of Nottingham. The Portable Antiquities Scheme has also recorded a broad spread of gaming pieces throughout the Danelaw. These pieces are usually roughly conical in shape and could have been cast very quickly and easily in simple moulds. Gaming pieces could be made of glass, like some found at Birka in Sweden, amber, liked those from the Skamby ship burial, or of horn or antler. Some of the Lewis chess pieces may actually have served double function as tafl pieces too. Analysis of gaming pieces and their deposition in graves suggests that each person was not buried with enough gaming pieces to provide both sides in a tafl game. Instead, they could provide a force for the attacker on an 11×11 board, on average, or the defender on a board as large as 15×15 squares. This suggests that Vikings brought their own force to the table rather than one person providing both sides. One final piece of evidence for board gaming is the depiction of two people playing a game and drinking horns of ale on a runestone (Gs 19) at Ockelbo in Sweden. The original stone has been destroyed but a replica stands on the spot now and shows clearly that the game board had the centre and the four corners marked to show where the hnefi or king stood at the start and where he had to escape to. Sore losers So, how did these games go down at parties? Óláfs saga helga (Chapters 152-53) in Heimskringla (pdf link) relates the tale of how one game played out at a feast at Roskilde in Denmark. Knútr the Great, king of England and Denmark, and he who tried to turn back the waves, was asked by his brother-in-law if he would like to play a board game. Knútr accepted but played badly. He was in a foul mood anyway, and got into a worse mood when Úlfr checked one of his pieces. He took his piece back, saying that he would make a different move instead. Úlfr got angry and tipped the board over, before storming out after they exchanged insults. The next morning, Knútr was getting dressed when he told his servant boy to go and kill Úlfr. The boy returned saying that Úlfr was in the church so he could not do it. Next Knútr told a Norwegian called Ívarr to kill Úlfr. Ivarr went into the church and ran Úlfr through with his sword. He returned to Knútr and told him the news. Heimskringla tells us that Knútr said to Ívarr “You have done well” but I prefer to imagine Knútr saying instead, “Checkmate!” If you are interested in trying hnefatafl cheaply, Cyningstan has a number of print-and-play hnefatafl variants.

Read More

Item

Croxall

Croxall, historically in the Repton and Gresley Hundred of Derbyshire, probably comes from the Old English male personal name Croc derived from the Old Norse personal name Krókr and the Old English halh ‘nook, corner of land’. However, it is also possible that the first element is from the Old English topographical element croc ‘crook’, perhaps ‘nook’. The parish was transferred to Staffordshire in 1894.

Read More

Blog Post

Some Derbyshire Warriors

Of the East Midlands counties, Derbyshire is perhaps the least well known for its Viking Age remains, apart of course from the camp at Repton. There is a scatter of place-names that suggest that members of that camp settled down in the region. And the recent publication of the Derbyshire volume of the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture provides further clues. Cross-shaft from Brailsford, Derbyshire. Photo by Judith Jesch At Brailsford, not far from Derby, a moss-covered cross-shaft stands outside the church, depicting a figure with a small shield and a rather large sword. The Corpus volume describes this as a ‘battle-ready warrior’ (p. 91) and suggests (p. 157) that this unusual warrior image is a memorial stone or marker of a member of the Anglo-Scandinavian warrior elite. The stone is loosely dated to the tenth century, so it could represent someone who had been at Repton, or more likely one of his descendants. Another warrior figure can be found on a cross-shaft at Norbury, to the west of Brailsford. This figure has a sword and what looks like a horn. The Corpus volume suggests (p. 194) that this is similarly a memorial to a member of the warrior elite. But it also raises the intriguing possibility that the figure represents the Norse god Heimdallr, whose horn announces the beginning of Ragnarök. While a bit speculative, this is not impossible since Heimdallr is fairly certainly represented on the Gosforth cross in Cumbria and possibly on the Jurby cross in the Isle of Man. Part of cross-shaft from Bakewell. Photo by Roderick Dale Though there seem to be only two warrior-figures from Derbyshire, there are plenty of other Anglo-Scandinavian sculptures. There are (or were) two hogbacks: one from Repton which is lost but known from drawings, and one from Derby which can be seen in the museum there. There are a number of crosses and cross-shafts with various types of Viking Age ornament. Particularly interesting is part of a cross-shaft from Bakewell with Borre-style ring-chain (p. 122). This type of ornament is associated with the Irish Sea region and demonstrates the links the East Midlands had with the rest of the Viking world. Who all these memorials represent is a fascinating question we would all love to know the answer to. Most intriguing of all is a rune-inscribed fragment, also from Bakewell. The runes are very clearly Anglo-Saxon, yet as interpreted by David Parsons (p. 142) they most likely represent the Scandinavian male personal name Helgi (or its female equivalent Helga).

Read More

Blog Post

Everyday Writing in Runes in Lincoln

(c) Christer Hamp, 2011, courtesy of The Collection, Lincoln Lincoln, in the first half of the tenth century: a time of intense political, social, and economic upheaval, with the English kings of Wessex battling to regain control of one of the last strongholds of Scandinavian power in eastern England. The late ninth century had seen the ‘Great Army’ of Vikings, which had arrived in England in 865, switch its energies from raiding to permanent settlement, the start of a process of colonisation that left a lasting imprint on the street-names of Lincoln and the place-names in the surrounding countryside. As the English gradually regained control of parts of the southern Danelaw in the early tenth century, drawing ever closer to Lincoln, the town’s Viking leaders looked to the North and the support of the powerful Norse dynasty established in York by Olaf Guthfrithson, who also ruled Dublin in the west. In the lower city, close to Brayford Pool and the River Witham, lie the halls and houses of the craftsmen and merchants who had followed in the wake of the first Scandinavian settlers, turning the town into an important and prosperous trading centre. In one of these houses, we might imagine a man, sitting next to the warm hearth, eating. Hungrily he strips all the flesh from the cattle ribs and, when finished, picks up his knife and starts cutting into the smooth, flat surface of one of the ribs, listening idly to the story that his brother is telling to the children, occasionally staring into the flames of the fire. As he listens, drinking ale from his leather cup, he fills the surface of the rib with the runic letters that had been taught to him by one of the men he’d worked alongside in Norway Less well known than the rune-inscribed comb-case also found in the city, this fragmentary inscription on a cattle rib – found in disturbed deposits in St Benedict’s Square, Lincoln – doesn’t contain a clear message that can be understood today. The rib is about 10 cm long and 3 cm wide at its maximum extent. It is fragmentary, missing its top half before the first word divider in the inscription, as well as the end of rib and possibly, therefore, the end of the inscription. The runes are inscribed from left to right along the length of the rib and say: (b) – – – – – l x h i t i r x s t i n x As can be seen from the photograph above, the tops of the first few runes are missing because the bone is broken there. The brackets around the first rune indicate that the rune is incomplete, but enough survives for it to be identifiable. The hyphens indicate runes of which traces survive and which can be counted, but which can no longer be identified. The two complete words, hitir and stin, could both be read in a number of different ways, as some runes represented more than one sound in the spoken language (the i-rune could also be used for e and ei, for example, while the b-rune might be used for words beginning with both b and p in Old Norse). hitir might therefore be read as the Old Norse verb heittir ‘heats’ or as heitir ‘is called’, and stin might be the noun steinn ‘stone’ or the personal name Steinn, but there are other possibilities, especially given our lack of knowledge of the kind of everyday language that might have been in use in Lincoln at the time. In casual inscriptions like this, names are often the most commonly found element, so perhaps the most likely interpretation is ‘[someone] is called Steinn-’, even if we don’t necessarily understand why this might have been carved onto a cow’s rib. However, we only have to think of the kinds of random doodles that we might make with a pen when, say, bored or only partly concentrating (while on the phone or watching TV, for example) to realise that not all written texts necessarily have to be in complete sentences or indeed make sense! Carved on a small piece of bone that would most likely have just been lying around after a meal, the rune carver may simply have been amusing themselves or practising or even absentt-mindedly carving words that were being spoken at the time. This inscription is nevertheless valuable to historians, because it reminds us about the kind of everyday uses of language and writing which – more often than not – simply disappear from the historical record. Much of what survives from the past has been deliberately preserved and so represents something that was important or unusual or particularly valued, for whatever reason. Before archaeological excavations started to uncover hundreds of casual inscriptions like this across Scandinavia, it was thought that the Vikings mainly used runes for carving into stones and monuments to commemorate their dead, but now we know that this was not the case. Then, as now, often everyday texts and objects are discarded because they are so very common, and therefore considered unimportant or not worthy of preservation – think, for example, of post-it notes, shopping lists, or even school-work. This rune-inscribed rib from Lincoln therefore provides us with valuable evidence of the everyday use of runes in this part of the Viking world and, like place-names, is another reminder of the distinctive culture that Scandinavians brought with them to the East Midlands.

Read More

Viking Designs

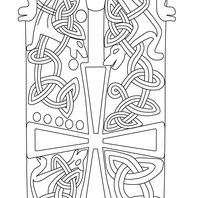

Details from the Hickling Hogback

Detail drawings showing elements of the designs on the hogback stone, a type of Anglo-Scandinavian grave cover, from St Luke’s Church, Hickling, Nottinghamshire.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Shovel

A reproduction wooden shovel based on fragments found at York.

Read More

Viking Objects

Reproduction Bone Dice

A pair of reproduction bone dice. Viking Age dice were usually rectangular rather than cubes, making it harder to roll the numbers on the ends of the dice. They do not follow the modern convention of having the numbers on opposite faces add up to seven. We do not know what games the people played with dice in this period, but it has been suggested that dice might have been used as part of playing board games like hnefatafl.

Read More

Blog Post

Saint Thorlak in Lincoln

Saint Thorlak in the Catholic Church, Reykjavik. (by Orf3us [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons)The first Icelander known to have studied in Lincoln was Þorlákr (Thorlak) Þórhallsson, bishop of Skálholt, South Iceland, from 1178 until his death in 1193. He studied abroad from c. 1153 – 1159, first in Paris and then in Lincoln. The reason he went to Lincoln is unknown. He may have met a master in Paris whom he followed to England. Another good reason might be that the cathedral school of Lincoln was well known at that time for the study of canonical law. He must have enjoyed his stay in Lincoln because his nephew, Páll Jónsson, followed in his footsteps and studied there as well. All sources on Þorlákr are written in the vernacular (Old Icelandic) except for remnants of Latin texts written shortly after 1200. Three versions of Þorláks saga (The Saga of Thorlak) have been preserved. The oldest version of the Icelandic Þorláks saga was composed about the same time as the Latin texts. Þorláks saga describes the bishop as a pious man in a hagiographic fashion, but it also tells of his disputes with chieftains about church ownership and moral issues. To his dismay, one of the country’s most powerful chieftains kept Þorlákr’s sister as a concubine. Their son was the aforementioned Páll Jónsson who succeded Þorlákr as bishop of Skálholt. As bishop, he permitted people to invoke his uncle Þorlákr as a saint. Þorlákr’s miracles were gathered and written down in a book, still preserved in a 13th-century manuscript. The original version of the miracle-book was read aloud at the Alþingi in Þingvellir, in 1199. Þorlákr seems to have been a popular saint until the reformation. Today, Icelanders mainly remember him because of his feast-day, December 23rd, the day when people are making their final preparations for Christmas. The day is still called Þorláksmessa, the Mass of St Þorlákr. The Viking Society for Northern Research has a freely downloadable pdf translation of The Saga of Bishop Thorlak (Þorláks saga byskups) if you wish to read more about him.

Read More

Viking Names

Ravensdale Park

Ravensdale Park, in the Appletree Hundred of Derbyshire, clearly derives its name from either the bird or a person with a name that corresponds to that of the bird, but its linguistic origin is difficult to pin down because of the similarities between Old Norse and Old English. The first element could be Old Norse hrafn ‘raven’, or the Old Norse male personal name Hrafn, or Old English hræfn ‘raven’, or the Old English male personal name Hræfn. The second element is either Old Norse dalr ‘valley’ or Old English dæl ‘a pit, a hollow; later a valley’. It was one of the parks of Duffield Frith hence the later affix ‘park’. In the Nottinghamshire place-name Ranskill, the first element is more likely to be Old Norse as the second element is also in that language, but the difficulty of deciding between the bird and the personal name Hrafn is the same.

Read More

Viking Names

Swarkestone

Swarkestone, in the Repton and Gresley Hundred of Derbyshire, is derived from a Scandinavian male personal name which appears in Old Danish as Swerkir, in Old West Norse as Sorkir and in Old Swedish as Swerker. This is combined with Old English tun ‘farm, settlement’ and it is thus a hybrid name, as so many in the Trent Valley.

Read More

Viking Names

Ketsby

Ketsby, in the Hill Wapentake of Lincolnshire, comes from the Old Norse male personal name Ketill and the Old Norse element by ‘farmstead, village’. It is a joint parish with South Ormsby.