Winter Camps in the East Midlands: Location and Layout

by William Pidzamecky, University of Nottingham

Posted in: Archaeology, East Midlands, Viking Age, Vikings

Our knowledge of the Viking Great Army’s movments during its campaigns in England is provided by entries in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a compilation of annalistic entries that describe events in a particular year. Despite some drawbacks to using the chronicle as a source, it does provide a roadmap for where the Vikings stopped for the winter. In fact, these were termed wintersetl by the compilers of the chronicle otherwise known as winter camps. Two of the winter camps mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are under current investigation, Repton and Torksey.

© P L Chadwick, via Geograph, CC BY-SA 2.0

Both winter camps are located along a river which would have provided the Viking inhabitants with vital transportation links required in most raiding or trading activities. It would also seem likely that the waterways were selected in order to provide a natural defensive element to the settlement, usually alongside another natural feature such as a raised promontory or a marsh, or an easy means of escape if the settlement was overwhelmed. In addition, the winter camps seem to be placed in relation to recently captured territory which makes sense for force out on campaign.

Viking invaders took Repton and immediately constructed a D-shaped wall using the pre-existing church as a gatehouse. The remnants of this wall were discovered in the 1970s and 1980s in the form of a V-shaped ditch, calculated to have been about 8m wide and 4m deep, cutting through the earlier Anglo-Saxon monastic burials (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 57, 59; Jarman 2018a, 29). The 1979 excavations revealed four successive ditches; the V-shaped ditch with a flat narrow bottom was the earliest and was backfilled shortly after being dug (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 58). The ditches have been dated to between the Group 2 Middle Anglo-Saxon and Group 3 Post-Viking burials, which fits with late ninth-century ‘Great Army’ occupation (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 59).

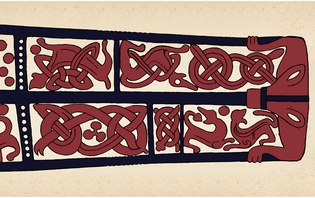

A Viking sword found at Repton, Derbyshire. (c) Derby Museums 2019

Unlike Repton, in Torksey Vikings only utilized natural defences, such as the river Trent and the wet marshy ground, which turned the settlement into an island (Hadley and Richards 2016, 32; Raffield 2016, 313). Despite not having any walls or ditches, it is likely that the ‘Great Army’ would have found the water and marsh defence sufficient in light of their recent peace with Mercia (Raffield 2016, 323).

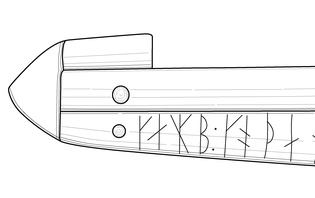

A quarter of an imitation Carolingian gold solidus found near Torksey, Lincolnshire. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

In terms of buildings there is a general lack of evidence for permanent structures at both Torksey and Repton. It is unclear whether this is due to poor preservation, need for more archaeological investigation, or that they truly did not exist. The use of Repton, Torksey, and the other wintersetl as army bases during campaigning probably explains the lack of permanent dwellings and workshops from their foundation but does not explain why none were built throughout the rest of their occupation when the army left.

The lack of urban planning and systems of streets and plots likely has to do with either a lack of refinement in terms of the methodology and ideas behind settlement foundation which requires more experience over time, the motivations and needs surrounding the foundation of a settlement, or even a combination of both. As mentioned above, the wintersetl in England were created, primarily, to house a military force on campaign, which moved on very quickly after the settlement was established. Therefore, it would not make sense to spend time and resources developing a systematic layout nor to begin the time-consuming process of building permanent structures.

References:

Biddle, Martin, and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle. 2001. ‘Repton and the “Great Heathen Army”, 873–4’. In Vikings and the Danelaw: Select Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress, edited by James Graham-Campbell, Richard Hall, Judith Jesch, and David Parsons, 45–96. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Hadley, Dawn, and Julian Richards. 2016. ‘The Viking Winter Camp and Anglo-Scandinavian Town at Torksey, Lincolnshire – the Landscape Context’. The Antiquaries Journal, no. 96: 23–67.

Raffield, Ben. 2016. ‘Bands of Brothers: A Re-Appraisal of the Viking Great Army and Its Implications for the Scandinavian Colonization of England’. Early Medieval Europe 24 (3): 308–37.