In this area we present our blog posts on a variety of Viking subjects from a variety of authors. Please scroll down or use the filter to look at specific subjects…

Explore our blog posts...

Havelok the Dane

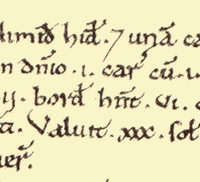

The Middle English romance Havelok the Dane was written around 1300 for a Lincolnshire audience still aware of its Viking heritage. It tells the story of Havelok, the son of the Danish king Birkabeyn, who as a small child is imprisoned after his father's death along with his sisters. Their supposed guardian kills the sisters, but Havelok escapes through the help of a kindly peasant called Grim. This Grim eventually takes his whole family, including Havelok, to England, where he founds the settlement known as Grimsby. Havelok eventually marries an English princess called Goldboro and becomes king of all England. Written from a later medieval perspective, the poem's primary purpose is to celebrate the harmoniously dual Anglo-Saxon and Viking heritage of the English nation, and to acknowledge the full assimilation of the Danish-origin inhabitants into this nation. Havelok's trajectory from prince to pauper and back again is a common romance motif and the story should not be taken too literally. But it does plug into local memories of the Danish migration to Lincolnshire. As an explanation for this migration, the tyranny of the Danish ruler presented in Havelok parallels the role of Harald Finehair in Norway, whose tyranny is presented in the Icelandic sagas as having been the main cause of the emigration to Iceland. Even though Grim is a fictional character, the passage in the poem which explains how he arrived and how Grimsby came to be named after him has the ring of truth. It describes how he sailed into the Humber at the north end of the province of Lindsey. There he settled and built a small house. Because he owned the place, it took its name from him and has been called Grimsby ever since: In Humber Grim bigan to lende, In Lindeseye, riht at þe north ende. Þer sat his ship up-on þe sond, But Grim it drou up to þe lond; And þere he made a litel cote To him and to hise flote. Bigan he þere for to erde, A litel hus to maken of erþe, So þat he wel þore were Of here herboru herborwed þere; And for þat Grim þat place auhte, Þe stede of Grim þe name lauhte; So þat Grimesbi it calle He þat þer-of speken alle; And so shulen men it callen ay, Bituene þis and domesday. The stone plaque shown above, which is derived from the thirteenth-century town seal of Grimsby, depicts Grim as a warrior in the middle, with the crowned figures of Havelok to the left and his bride Goldboro on the right. Havelok the Dane Database of Middle English Romance Eleanor Parker, Dragon Lords. The History and Legends of Viking England. London: I.B. Tauris, 2018.

Read More

A Poet Visits Grimsby

Grimsby is one of the few places in the East Midlands mentioned in an Icelandic saga. In Orkneyinga saga the Norwegian poet (and later Earl of Orkney) Rögnvaldr Kali Kolsson joins up at the age of fifteen with a group of Norwegian merchants for his first trip abroad. The date of this is uncertain, but it was probably around 1130. The saga says (ch. 59) that there were a lot of people there from Orkney, the Hebrides and from mainland Scotland. In Grimsby, according to the saga (and it's the only saga that has this anecdote), Rögnvaldr meets an Irish-Hebridean called Gillikristr who claims his real name is Haraldr and that he is the son of the Norwegian king Magnús Barelegs. It's a blind anecdote, since nothing comes of it, and Gillikristr is never mentioned again, but the two part on friendly terms. The real reason for the anecdote in the saga is to introduce one of Rögnvaldr's poems (ch. 60). He was an excellent poet - 32 of his stanzas survive and many of them are justly famous. Unfortunately, his poem on Grimsby does not present a flattering picture of the place, rather it expresses the poet's delight to be heading back to Norway across the refreshing waves after five weeks in a muddy Grimsby (text and translation from Jesch 2009): Vér hǫfum vaðnar leirur vikur fimm megingrimmar; saurs vasa vant, es vôrum, viðr, í Grímsbœ miðjum. Nús, þats môs of mýrar meginkátliga lôtum branda elg á bylgjur Bjǫrgynjar til dynja. We have waded the mud-flats for five mightily grim weeks; there was no lack there of muck when we were in the middle of Grimsby. Now it is the case that mightily merrily we cause {the elk of the prow} [SHIP] to boom on the waves to Bergen across {the marshes of the gull} [SEA]. Although unflattering, the poem is probably accurate. The coastal landscape around Grimsby is characterised by both mud-flats and salt-marshes and the town itself was virtually an island with only one road into it at the end of the Middle Ages. The stanza appears to describe the Norwegians’ daily journey across the mud-flats to the town from their mooring-place in the haven during their five-week business trip. The sea-kenning mýrar môs ‘marshes of the gull’ is ironic since the sailors have left the marshes behind and the contrast is underlined by the two descriptors in megin- ‘mightily’, which contrast the grimness of their weeks in Grimsby with their pleasure at setting off for home. Supported by the poem, the anecdote confirms that, even after the end of the Viking Age, the Scandinavian parts of England still had extensive contacts with other parts of the Viking diaspora, in this case merchants from Norway and Scotland. Finnbogi Guðmundsson (ed.) 1965. Orkneyinga saga. Íslenzk fornrit 34. Reykjavík. Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards (trans.) 1978. Orkneyinga saga. Penguin. Jesch, Judith (ed.) 2009, ‘Rǫgnvaldr jarl Kali Kolsson, Lausavísur 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 577-8.

Read More

The Danelaw: a place or an idea?

The Danelaw: a place or an idea? This question was posed by Melvyn Bragg in a recent edition of In Our Time on Radio 4. The correct answer is ‘a bit of both’. But it’s a very good question and one worth a bit more exploration. As an area, the Danelaw is often thought to have been established in the treaty made at Wedmore between King Alfred and the Viking leader Guthrum in the 880s. While only recorded in later manuscripts, it is generally accepted as a true record of what was just one of several treaties between English rulers and Viking leaders at the time. The treaty is rather specific in being between ‘King Alfred and King Guthrum and the council of all the English nation and all the people which are in East Anglia’. It defines a boundary which goes ‘up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then straight to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street’. In this way the treaty delineates the area within which the provisions of the treaty apply but does not define who is in charge there. The provisions themselves are quite basic and are to do with the relationship between Danes and English, in cases of manslaughter, the purchase of men, horses or oxen, and recruitment to either army. In all the treaty is a practical, and limited, agreement which makes no assumptions about who occupies or holds the defined territory, which is in any case quite vague about how far north it might extend. There is also no suggestion in the treaty of any difference between ‘Danish’ and ‘English’ law, in fact the treaty takes pains to assess the compensation for the manslaughter of an English or a Danish man at the same amount. The idea that there are two legal jurisdictions, in which that of the Danes, or of Danish-held territory, is distinct from its English equivalent, does not become clear in documents until the early eleventh century. In these, lagu ‘law’, an Old Norse word introduced into Old English by Archbishop Wulfstan, collocates with the ethnonym Dena to express the idea of the ‘law of the Danes’, but the term is not yet a compound as in ‘Danelaw’. For example, in Æthelred’s law code (VI) of 1008, Wulfstan distinguishes between on Ængla lage 7 on Dena lage be þam þe heora lagu sy. This might be translated as ‘in the jurisdiction of the English and in the jurisdiction of the Danes according to what their legal practice might be’ and there are several similar uses of the term around this time. What this shows is that there is an idea of a Scandinavian (or Anglo-Scandinavian, as argued by Lesley Abrams) legal province within the English kingdom. This province is presumably territorially defined, though this is not actually indicated in the legal codes themselves. An earlier code of Æthelred (III, from around 1002, known as the Wantage code), does not use the Danelaw term but does mention the Five Boroughs and makes extensive use of Scandinavian legal language in legislating for that region. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in a poetic entry for 942, makes a distinction between the Danes of the Five Boroughs (Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford) and the Norsemen who ruled north of them and from whose subjugation the Danes were freed by King Edmund. All this suggests that the Scandinavian legal province recognised in the law codes of the time reached only as far as the Humber, but that the legal distinctions between Danes and English were still important (and recognised) in the eleventh century, some 50-100 years after English rulers had conquered the Scandinavian-ruled areas during the tenth century. So, ‘Danelaw’ is not a term for the area defined in the treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. Also, as a legal concept it appears only to apply to an area south of the Humber, more specifically perhaps just the region of the Five Boroughs. However neither of these is how the term is most commonly used today. Despite its origin in the law codes of the early eleventh century, today the term is most frequently used in a more general way, without necessarily any reference to law, jurisdiction or even a well-defined area. Most commonly it is used to refer to that part of England which was, for want of a better word, ‘influenced’ by the activities of Scandinavians, whether they were the so-called ‘Great Heathen Army’ of the ninth century or peaceful settlers in the tenth. It is only after King Cnut became king of all England in the eleventh century that the distinction between ‘Danish’ and ‘English’ England becomes hard to sustain. The reign of Cnut and, briefly, his son Harthacnut brought new Scandinavian incomers to England, who often reached parts of England not otherwise thought of as falling within the ‘Danelaw’ and the overall picture is quite different. To use the term ‘Danelaw’ in this general sense is actually quite misleading. It implies that only Danes were involved in the Scandinavian impact on England, and that, whether idea or area, it is mostly about law and jurisdiction. But many scholars use the term in contexts where they are looking at the Scandinavians’ influence on settlement, culture both material and immaterial, and language, as well as their impact on church and society. Evidence for this influence and impact can be found in large parts of eastern and northern England, including regions far from the area described in the Treaty of Wedmore, or the Five Boroughs. Areas in the north-west, such as Cumbria, have plentiful evidence of Scandinavian influence in burials, metalwork, place-names, dialect, sculpture and runic inscriptions, yet there is almost no documentary evidence for how this Scandinavian influence came about. Is Cumbria part of the Danelaw? It was certainly part of the great Viking diaspora that affected much of England from the ninth to the eleventh (or even twelfth) century, yet the term ‘Danelaw’ does not seem entirely appropriate to describe that region in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Perhaps it is best to use the term ‘Scandinavian England’ (as in the title of an important collection of essays by F. T. Wainwright). Even better would be ‘Anglo-Scandinavian England’, since even the areas most heavily influenced by the Scandinavian incomers never completely lost their Anglo-Saxon inhabitants, material culture, customs or language. But although the term ‘Danelaw’ is inadequate, we should not completely forget it either. At the very least it reminds us that those supposedly lawless Vikings actually gave the English language its word for ‘law’, as still used today. References: Lesley Abrams, ‘Edward the Elder’s Danelaw’, in Edward the Elder 899-924, ed. N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 128-43. Lesley Abrams, ‘King Edgar and the men of the Danelaw’, in Edgar, King of the English 959-975, ed. Donald Scragg. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008, pp. 171-91. Katherine Holman, ‘Defining the Danelaw’, in Vikings and the Danelaw, ed. James Graham-Campbell et al. Oxford: Oxbow, 2001, pp. 1-11. Sara M. Pons-Sanz, Norse-Derived Vocabulary in Late Old English Texts, Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2007, pp. 70-72. Simon Trafford, ‘The Alfred-Guthrum treaty’, in Cultures in Contact. Scandinavian settlement in England in the ninth and tenth centuries, ed. Dawn M. Hadley and Julian D. Richards. Turnhout: Brepols, 2000, pp. 43-64. F. T. Wainwright, Scandinavian England, London: Phillimore, 1975. Dorothy Whitelock, English Historical Documents I. c. 500-1042. London: Routledge, 1996 [2nd ed.]. Early English Laws http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/

Read More

The Culinary Habits of Viking Age England

Though today we are well aware that food can be a luxury, a treat, a lifestyle, even a touchstone for memory, archaeologists looking at past diets have often seen everyday food in largely nutritional terms (in contrast to the focus given to the food of ritual, feasting, and assembly). Our experience in the contemporary world, together with information from historical and ethnographic account, tells us that food is central to the production of identity, having symbolic qualities, and often acting as a kind of social glue. In contexts of social change - such as urbanisation, religious conversion, migration and culture contact - we might expect it to play a particularly important role. The Viking Age, then, looks like a particularly promising context for a study of such phenomena. How did cooking and eating work to bring together the household? What were its social qualities in contexts of feasting and exchange? Perhaps most interestingly of all, what was the role of cuisine in the context of diaspora? What might the stubbornness or mutability of ethnically derived habits of cooking and eating tell us about relationships between natives and newcomers, or between migrants and their homelands? Such questions have proven difficult to answer using traditional archaeological approaches. The study of animal bones can tell us which animals were being eaten, how they were husbanded, butchered, and provisioned, but generally fall short of revealing much about the fine detail of food preparation or consumption. Fruits, vegetables, grain, nuts, seeds and spices are recovered from archaeological sites where preservation conditions allow, but their relationship with animal products is unclear. The sequences excavated in medieval towns rarely provide us with the undisturbed 'culinary contexts' that would allow us to reconstruct an individual meal. These environmental data thus provide us with information that is fundamental to answering the kinds of questions we are interested in, but are insufficient in isolation. We need a more high-resolution, interdisciplinary approach, that draws not only on this information, but also on inference drawn from a range of documentary sources, and from new insights that might be delivered through natural scientific approaches. In particular, there is considerable potential to explore the relationship between food and the material culture used to store, prepare, and present it, and how these phenomena varied in time and space. This is the task of Melting Pot: Food and Identity in the Age of Vikings. This AHRC-funded project has applied leading-edge scientific techniques to characterise the mode of use of different forms of pottery (patterns of sooting and burning can tell us about styles of cooking), and to analyse the contents of the pots (microscopic examination of burnt-on food crusts can reveal the presence of plant remains, fish scales and the like, while chemical analysis of the fabric of a pot can help us to identify the presence of now invisible fats, oils and waxes). Together, we are able to build something like a biography of a pot: what use was it intended for, how did it sit in the hearth, what was cooked in it, and how? We have undertaken the largest scientific survey of Viking-Age pottery to date; by analysing hundreds of identifiable sherds from well-dated contexts across England, we will be able to paint a picture of how the people of Viking-Age England were preparing and eating their food. How different were cooking habits in the commercial centres of towns like York from what we see on their peripheries? How does this urban picture compare with the situation in the rural hinterlands? To what degree is there a common urban diet in the towns of the Danelaw? How much does this differ from what we see in Saxon London? Is there evidence of change over time, and can these be related to patterns of migration, local politics, long-range economics, or urban development? How does the situation in England differ from what we see from contemporary sites across Scandinavia? Our lab work is complete, and we are now starting to find answers to these questions. A key element of the project is communicating its findings and significance with a range of audiences, and with this in mind, we have put together two exhibitions. The first, undertaken in collaboration with the York Archaeological Trust and A-level students from York College, is based on experimental cooking and biomolecular analyses undertaken by the students, opened at DIG, York on 1st February. The aim is to showcase the potential of science to answer archaeological questions. Later this month will see the launch of a parallel exhibit at The Collection, Lincoln, which will introduce the public to material from excavations in the city that has rarely been displayed, and discuss what these artefacts and ecofacts can tell us about Viking-Age cuisine. We have talks and workshops planned at both venues, starting with sessions at York's Viking Festival. In addition, we have put together a range of teaching resources for Key Stage 2 History, which we will soon be releasing. For more details on these, and all other aspects of the project, please visit our website: www.meltingpot.site, or follow us on Twitter: @foodAD1000.

Read More

Unlocking the Meaning of Keys in the Viking Age

Most keys that have been found are from graves, and were deliberately buried with individuals. The fact that only some people were buried with keys shows that keys had both practical and symbolic functions in the Viking Age. The practical function of keys was to lock locks, as is to be expected. They secured items against access or theft, and their presence indicates that the owner of the key actually had valuables worth locking up. Viking Age keys, padlocks and locks have all been found by archaeologists. The locks and padlocks probably belonged to chests and were used to secure a person’s most important belongings. Chests were used as storage at home and as travelling luggage by sailors going abroad. The chest provided a secure place to keep personal belongings, and was also used as a seat for the rowers. Keys could be decorated, like one from Gjerdal in Norway, which had been decorated with stylized animal heads and geometric ornamentation that dates it to the Viking Age. Keys are found as a part of burial paraphernalia in Scandinavia from the Migration Period through the Viking Age, and were usually made of iron or copper alloy. Although often viewed as primarily grave goods, in reality they have also been found on settlement sites throughout Scandinavia, and as single finds. Received wisdom states that they are most commonly found in women’s graves, and occasionally in men’s graves. However, they are not a common find overall. Only a small number of keys have been found compared to the large number of excavations undertaken. Most importantly, this applies to graves, where Berg (2015, 130) notes that of 6000-8000 graves excavated in south-east Norway only 117 contained keys. She also shows that keys are not a predominantly female accessory, as is usually stated. The Museum of Cultural History in Oslo notes that approximately 75 copper alloy keys and 170 iron keys of Viking Age date have been found in south-east Norway alone. The copper alloy keys are all different, showing that they were not mass-produced, but rather cast individually. Moulds for keys and smiths’ tools have been found during the excavations at Kaupang in Norway, providing the key to understanding how keys were made. Keys had symbolic value which has most often been taken to indicate the social function of the bearer. As items that provided access and closed it off, they indicated that the bearer had these powers too. This symbolic value has been most associated with women, largely because medieval law codes such as Borgartingslova (the Borgarthing Law) which dates from the twelfth or thirteenth century, identify keys 'as a signifier for the key-bearer, sometimes described as a woman or housewife' (Berg. 2015, 127). In the Eddic poem Þrymskviða Thor must dress up as Freyja. Part of his disguise is a set of keys hanging from his belt leading to the suggestion that Freyja may have been particularly associated with keys as a symbol of her domain. This image of powerful women controlling access to the house has led to an enduring image of the Viking Age matriarch wearing keys on her belt or hanging from a brooch to show that she was the gatekeeper in the household. However, this raises the question of what keys are doing in men’s graves, as in the case of Grave 541 at Repton, Derbyshire. Norse laws from the medieval period demonstrate that keys symbolised control over the household, a female area of power, and reinforce this idea. Given that keys symbolized power, ownership and control of access, it is likely that keys in men’s graves are indicators of their status as owners too. They may not have carried them in life, but keys as grave goods symbolise their power after death. Beyond simple interpretations of keys indicating ownership, Pantmann (2014, 52) suggests that keys had a cultic role in pagan Scandinavia. The concept of the ‘kloge kone’ or ‘wise woman’ may have been symbolised by keys, because keys have a universal symbolic value indicating knowledge, power, and insight. In this role, they are associated with Freyja and thus childbirth, the afterlife (Freyja receives half of those slain in battle into her hall Sessrúmnir), and female leadership, a role that is closely associated with the role of matriarch of a household. Berg (2015, 127) notes that the connection between keys and childbirth is that the keys symbolically unlock the womb or loins to ensure a successful birth. Keys are also associated with Christianity. The triquetra found on some keys may be associated with the Holy Trinity, but may also be a pre-Christian symbol of fertility and motherhood (Berg, 128). The focus on keys as symbols of women’s power is not supported by the archaeological evidence, so it is likely that keys are not symbolic of the housewife alone. However, it is noteworthy that decorated bronze keys are almost exclusively linked to women while iron keys are not (Aannestad. 2004, 80). The fact that keys were buried with certain people is a clear indicator of symbolic significance; the dead are buried with items that are important to them or to those that buried them. Those items gain significance by being chosen to be included as grave goods. Thus keys had symbolic significance, and it may have been related to power and access. This is supported by their rarity as finds, indicating that they belonged to the few, not to the many, and it is likely that those few were the ones who had wealth or treasures that needed locking away. Keys are symbols of wealth and access to power, and perhaps symbolise the ability to affect one’s environment through ritual action (Berg. 2015, 132), but their use as symbols is nuanced and may represent different things at different points in the Viking Age, and in different places within the Viking diaspora. As a result, unlocking the meaning of keys in the Viking Age is not simple. Further Reading: Aannestad, Hanne Lovise. 2004. “En nøkkel til kunnskap – Om kvinneroller i vikingtid”. Viking. Berg, H. L. 2015. “'Truth' and reproduction of knowledge. Critical thoughts on the interpretation and understanding of Iron-Age Keys”. In Marianne Hem Eriksen, Unn Pedersen, Bernt Rundberget, Irmelin Axelsen and Heidi Lund Berg (eds). Viking Worlds: Things, spaces and movement. Oxbow Books: Oxford. Pantmann, Pernille. 2014. “Nøglekvinderne” in Kvinner i vikingtid. Ed. by Nancy Coleman and Nanna Løkka. Scandinavian Academic Press: Oslo. Pp 39-56.

Read More

Slithering Swords in the Viking World

Forget Vikings and The Last Kingdom – the most pulsating depictions of Viking Age battle appear in early medieval Scandinavian poetry. Here, armies transform into elemental forces and fierce creatures, clashing together in a mass of noise and light. Popular in this imagery is the likening of swords to snakes, with poets styling these weapons as ‘wound snakes’ and ‘battle snakes’ that bite at their enemies. This was not just poetic flourish. Real Viking swords also had something of the snake about them. Their pattern-welded blades writhe with sinuous designs, their hilts with looping serpents. Scale-like panels encrust the heavy hilts of Petersen’s Type D swords; one from Trælnes, Norway even has dark diamonds on a brighter background, mirroring the dark-on-light streak along an adder’s back. Similar designs were made with inlaid wire on other swords. It is even tempting to ponder whether coiled-up blades in Viking burials evoked the posture of resting snakes. How and why did this union between swords and snakes come about? Well, both are long, thin, bulbous at one end and tapered towards the other; they are glossy with mottled markings; both shed their skin (or scabbard); they weave about and bite when threatened. This would be an elegant explanation if snakes were just ‘snakes’, shall we say; but in Viking Scandinavia, serpents held immense symbolic significance. They permeate Scandinavian cosmology, from the ‘world serpent’ Jǫrmungandr to Óðinn using a snake’s form to steal the mead of poetry. Clearly, poets did not just liken swords to snakes because they looked a bit similar. So, what was going on? Poets often paired snakes with key symbols of power and status in the Viking world, namely arm-rings, gold and ships. Swords behaved similarly in Viking thought, so it is perhaps no surprise that snakes dominate their description and decoration. But the ambiguity surrounding snakes may also have been a factor. In Norse mythology, serpents represented both order and destruction (Jǫrmungandr binding the world together, then running rampant at Ragnarǫk). Similarly, in the poem Rígsþula Heimdallr’s highest born child has ‘piercing’ eyes ‘like a young snake’s’, but in Skirnismál the ‘shining serpent’ is ‘hateful to men’. Such contrasting feelings also applied to swords, which were instruments of order (protecting one’s self, comrades, kingdom) and chaos (destroying those of your enemy). This tension is captured by a Valkyrie in the poem Helgakviða Hjǫrvarðssonar, who knows a sword that is ‘better than all the rest’ – but it is also ‘the evil one among battle-needles’. This verse may encapsulate why swords and snakes intertwined in Viking minds: two powerful beings that were at once alluring and deadly. References Brunning, S., '"(Swinger of) the Serpent of Wounds": Swords and Snakes in the Viking Mind' in Representing Beasts in Early Medieval England and Scandinavia, ed. by Michael D. J. Bintley and Thomas J. T. Williams (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2015)

Read More

Watling Street, the Danelaw and the East Midlands, part 2

If you've not read the first part of this blog post, you can find it HERE. Why, in 1013, was the Danish king, Svein Forkbeard, able to rely on the support of what is described as the here – the raiding army – north of Watling Street, long after the ninth-century Viking armies had dispersed and settled, and northern and eastern England had apparently been integrated into the kingdom of England? It seems that the reality on the ground was rather more complex than Alfred’s successors would have us believe. For example, Edward the Elder issued a law code which clearly distinguishes between the rules on compensation ‘herein’ (in his own kingdom) and in the north and the east, the latter of which were instead determined by ‘the provisions of the treaties’ (in the plural). This clearly reflects the fragmented political landscape within these areas, at least before Edward’s campaign of 917. Edgar – while proclaiming his rule over a ‘united’ England – also allowed his Danish subjects considerable legal freedoms: ‘there should be among the Danes such good laws as they best decide on’. It is interesting to note that the first reference to distinctively Danish laws operating in England is found in a legal code issued by Archbishop Wulfstan of York in 1008, just a few years before Svein landed in Lincolnshire. In this code, the legal process for a man defending himself against charges of plotting against the king (at this time, Æthelred II) is said to be different ‘for those under Danish law’. Æthelred II also issued a separate legal code for the Five Boroughs of Nottingham, Leicester, Lincoln, Stamford, and Derby a little earlier, around 997. Although the areas covered by this document were considered to be part of England and under the rule of the English king, much of this law, known as the Wantage Code, aimed to extend English legal practice into the Five Boroughs. This suggests that legally, at least, important differences remained between ‘England’ and the ‘Danelaw’, which are underplayed in sources associated with the royal court of Wessex. The place-name map bears perhaps the clearest witness to the importance of Watling Street as a dividing line between English and Scandinavian zones, showing how very few settlements with Scandinavian place-names can be found south of its line. This seems to suggest that – whatever the number of Scandinavian settlers – at the time when most of these names were given, Watling Street must have operated as some kind of border, whether that was formally established through treaties or informally observed. This is perhaps not surprising, given that there is plenty of evidence for roads being used to delimit estate and parish boundaries in the Anglo-Saxon period. One of the difficulties in using place-name evidence to understand Viking settlement is that much of the evidence for Scandinavian place-names (and indeed for place-names in general) is first recorded in Domesday Book, William the Conqueror’s record of the land-ownership, taxable values, and population, that was assembled in 1086. This makes it difficult to know exactly when the names were given, and they therefore can’t specifically be linked to the period after the conquest of Mercia in the ninth century and before the re-conquest of the Danelaw. But what we can say is that the place-names certainly suggest that the language of the people living to the north of the line of Watling Street was heavily influenced by ‘the Danish tongue’ in the period before the late eleventh century when Domesday Book was compiled and, on the basis of Svein Forkbeard’s campaign in 1013, it seems likely that this division was already clear at the beginning of that century. It is nevertheless important to remember that, even in the areas lying to the north of Watling Street, between a half and two-thirds of place-names are English. The communities that were established in the ‘Danelaw’ can’t be easily defined as ‘Danish’ or ‘English’ or even ‘Anglo-Scandinavian’ – common sense suggests that there must have been considerable local variation, with there likely to be some pockets of heavily-Scandinavianised areas and others that were less affected. Domesday Book also reveals another clear difference in communities lying to the north of Watling Street in the late eleventh century: the proportion of people described as ‘freemen’ or ‘sokemen’ –essentially free peasants – as opposed to unfree cottars, bordars, and villeins. The Midlands counties of Warwickshire, Leicestershire and Northamptonshire formed a single administrative ‘circuit’ used by the Domesday commissioners, but while there are very few freemen recorded living on estates in Warwickshire, to the south of Watling Street, the numbers jump dramatically as soon as Watling Street is crossed, with freemen forming an important element in Leicestershire’s recorded population. In Northamptonshire, which is bisected by Watling Street, the same increase in the free population can be seen in the Domesday entries for estates lying to the north of Watling Street. An earlier generation of scholars, led by Sir Frank Stenton, saw the greater number of freemen in districts that had been affected by Scandinavian settlement as the descendants of huge Viking armies, who had hung up their axes and settled down to farm in the English countryside in the ninth century. Although this has long been rejected as too simplistic by historians, the distribution of these free peasants certainly suggests important social and legal conditions operated north of Watling Street, which is also hinted at in the earlier references to specifically Danish laws in northern and eastern England. As such, this evidence illustrates how Watling Street continued to mark a dividing line at the end of the eleventh century. Politically, legally, socially and linguistically, the East Midlands occupied a frontier zone, the importance of which continued to resonate through the Norman period. Useful sources: John Baker and Stuart Brookes (2013) Beyond the Burghal Hidage: Anglo-Saxon Civil Defence in the Viking Age. Leiden: Brill. Gillian Fellows-Jensen (1978) Scandinavian Settlement Names in the East Midlands. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag. David Hill (1981) Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell. Katherine Holman (2001) ‘Defining the Danelaw’ in James Graham-Campbell et al. (eds) Vikings and the Danelaw. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 1-11. Anna Powell-Smith and J. J. N. Palmer: Open Domesday. Available online: http://opendomesday.org Pauline Stafford (1985) The East Midlands in the Early Middle Ages. Leicester: Leicester University Press. Michael Swanton (transl. and ed.) (1996) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: J. M. Dent. University of London – Institute of Historical Research / Kings College London (2018) Early English Laws. Available online: http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/ Dorothy Whitelock (ed.) (1955) English Historical Documents c. 500-1042. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

Read More

Watling Street, the Danelaw and the East Midlands, Part 1

When Svein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, launched his invasion of England in 1013, he landed in Lincolnshire and, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, received the submission of Earl Uhtred and the Northumbrians at Gainsborough, followed by ‘all the people in Lindsey, and afterwards the people of the Five Boroughs [Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, and Stamford], and quickly after, all the raiding-army to the north of Watling Street’. This brief reference neatly highlights the geopolitical diversity of the East Midlands in the Viking period, listing the various local factions who allied themselves with Svein Forkbeard against the English king, Æthelred II. Importantly, it also suggests that Watling Street marked a clearly recognised border running through the former kingdom of Mercia, a point that is underlined by the Chronicler’s next statement that Svein ‘after he came over Watling Street […] wrought the greatest evil that any raiding-army could do’. The clear implication is that those living to the south of this old Roman road were seen as Svein’s enemies and treated accordingly. But, with the present political debates about hard and soft land borders in mind, how did Watling Street come to be seen as a political frontier running through the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia? Watling Street – or Wætlingastræt – is the name that the Anglo-Saxons gave to the road that the Romans built to connect Dover with Wroxeter. It cut a roughly diagonal line, perhaps as much as six metres wide, running from the south-east, via London and St Albans, to the north-west of the country, crossing central England. Built in the mid-first century AD, it clearly continued to be an important route through the landscape long after the Romans had left, not least to the ‘Great Army’ of Vikings that arrived in England in 865 and defeated the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia in 874. Watling Street – as well as other Roman roads – allowed these Viking raiders to move quickly across long distances, which must have been an important factor enabling their victories across far-flung parts of Anglo-Saxon England, and bringing about the rapid collapse of the kingdoms of East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia. The road still continues to divide the East Midlands from the West Midlands, preserved along much of the A5, which runs through Northamptonshire, and then forms the county boundary between Warwickshire and Leicestershire (with an important deviation that allowed Tamworth, lying to the north of Watling Street, to be incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon zone). As well as being mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1013, Watling Street is also mentioned in the treaty terms agreed by King Alfred the Great and his recently defeated Viking rival, Guthrum, sometime before 886, at a time when the last surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex was struggling for its survival. This agreement acknowledged clear spheres of control between the English and Danish leaders, and secured Alfred’s own kingdom of Wessex from the threat of Danish armies by recognising Guthrum’s control of East Anglia. The dividing line between Alfred’s and Guthrum’s kingdoms was outlined in some detail: ‘First concerning our boundaries: up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then in a straight line to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street.’ However, there is no suggestion in this treaty that the border continued to run north and eastwards along Watling Street through the Midlands, although some historians assume that this must have been the case. Instead, it looks like Alfred and Guthrum didn’t discuss the political situation in Mercia or attempt to define any boundaries there. This isn’t surprising as, of course, Guthrum wasn’t the only Viking leader harrying the English countryside in the ninth century, and other Viking leaders weren’t bound by the treaty terms agreed with Alfred. In 893, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers to various oaths and pledges given to Alfred by Northumbrians and East Anglians, as well as the activities of ‘other raiding-armies’. By the time the treaty with Guthrum was agreed, it is also evident that some of the Viking armies had become a permanent fixture in northern and eastern England, with references to them dividing up the land and settling down. Mercia seems to have been divided into two halves, east and west, with the western part being left under the control of Ceolwulf, while the eastern part was settled. As a key communication route, Watling Street, would no doubt have functioned as a convenient dividing line to all parties in working out details of any agreement in Mercia. However, it seems that any agreement was fairly short-lived, and certainly the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records how, after his death, Alfred’s son and daughter – Edward the Elder and Æthelflæd – campaigned north of Watling Street, trying to win back control of the area from the Viking armies. A series of fortified strongholds were constructed at key points across southern England, with those at Tamworth and Towcester representing English defensive points on Watling Street. By 921, ‘all the people that was settled in the land of Mercia, both Danish and English’ are said to have ‘turned to’ Edward, although this clearly glossed over the political realities of the continued struggle for control of the East Midlands. The arrival of Norsemen from Ireland around this time complicated the political landscape further, and one of their leaders, Olaf Guthfrithson, attempted to extend his control from York into the East Midlands. Following a devastating attack on Tamworth, Olaf met with King Edmund, Edward’s son, at Leicester, and Simeon of Durham records that their agreement in 941 specified that ‘Watling Street was the boundary of each kingdom’. But when Olaf died in the following year, Edmund captured the Five Boroughs and ‘conquered Mercia’. By the 960s, Alfred’s great-grandson, Edgar, was able to stipulate that his laws should ‘be common to all the nation, whether Englishmen, Danes or Britons’. The ‘Danelaw’ had apparently been reconquered by Alfred’s West-Saxon dynasty less than a hundred years after Alfred’s and Guthrum’s treaty and absorbed into a single political nation. So why, in 1013, was the Danish king, Svein Forkbeard, able to rely on the support of what is described as the here – the raiding army – north of Watling Street, long after the ninth-century Viking armies had dispersed and settled, and northern and eastern England had apparently been integrated into the kingdom of England? Find out in part 2 of this post.

Read More

Viking Leicestershire: The Artefactual Evidence, Part 2 Metal-detected Objects

Metal detecting is adding greatly to our knowledge of Scandinavian Leicestershire. At the time of writing, there are 130 objects recorded on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database that are Scandinavian in style, including coins (see blog) and objects now in museums (see part 1). Although recorded on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database, all finds discussed below remain in private ownership. The two most important finds are ‘Viking’ disc brooches. A gilded Jelling-style brooch from Melton depicts two gripping beasts (LEIC-36241D) and will be loaned to Melton Carnegie Museum in the spring . The other is a disc brooch from Cossington (LEIC-E7A016) with pseudo-filigree gilding which is rare in such brooches. Dr Jane Kershaw has identified this brooch as probably Danish from the late ninth or early tenth century, i.e. from the period shortly after the Great Army arrived and the Danelaw was established. There are three Anglo-Scandinavian Borre-style knot brooches from Leicestershire. These are made in a Scandinavian style but were manufactured in England. Their distribution, firmly within the Danelaw, suggests a ‘Scandinavian’ market for jewellery that reflected the styles of Scandinavia, hinting at nostalgia for the Scandinavian homeland and a desire to express Scandinavian identity. one was found just east of Melton (LEIC-782CD2), another at Goadby Marwood (LEIC-604DE5) and the last at Frisby on the Wreake (LEIC-CD4F45). This last place-name is interesting because it reflects the dominance of Old Norse in the area but points to the main settler there being Frisian and indicates that the Great Army was probably not purely Scandinavian. Some of the other artefacts recorded incude an unusual Borre-style triangular mount from Great Bowden (LEIC-48A221), very rare stirrup mount-like strap ends from Long Whatton (DENO-083C15) and Donington Le Heath (LEIC-982247), an unusual Urnes style strap end from Kirby Muxloe (LEIC-3E15B5), and a vertebral ring chain decorated strap end from Osbaston (LEIC-AE3855). Harness fittings and stirrup mounts make up about half the total and these are termed ‘Anglo-Scandinavian’. Some have direct Scandinavian parallels, some are thought to be locally made, influenced by settlement and possibly Cnut‘s reign. One rare type of stirrup mount, only found in eastern England occurs as a very rare pair from Peckleton, Leicestershire LEIC-8D1AC0 and LEIC-8C54F0. You can read more about these on the PAS blog. Lastly, we have two very rare and enigmatic objects. The first, a possible prick spur (LEIC-EEF651), from Loughborough among a small but significant scatter hinting at Scandinavian activity. It depicts a helmeted, drinking-horn-wielding man and has two parallels: both are from Germany, and it has been suggested the figure may be a Slavic God. How did it get to Loughborough? Given its suggested date range 900-1200, it could have arrived with a Scandinavian settler or it could have arrived later and be pure co-incidence it ended up near Scandinavian objects. The other is even more of a mystery (LEIC-0A4CB4). It may be a cart fitting, but it has no known parallels. Its decoration screams Viking with its gilded interlace, moustached face mask and triskele-wearing bearded beasts heads. You can read further discussion about it in a guest post by Dr Rena Maguire on our blog. I am excited to report that the finder is probably going to donate this so that it can go on display. These objects highlight the importance of recording with the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Each object is adding to a network of evidence that illuminates this period. They demonstrate the range of material culture that was popular in the Viking Age and point to enduring connections between the Danelaw and Scandinavia. The last two especially show that by recording a mystery we may eventually find a parallel and enhance our knowledge later.

Read More

Viking Leicestershire: The Artefactual Evidence, Part 1 Museum Collections

As part of the Danelaw with a county town listed amongst the Five Boroughs, Leicestershire is rich in Scandinavian influence. The county is littered with ‘Scandinavian’ place names (e.g. Harby) and we are lucky that chance finds and excavations in the city of Leicester have revealed a few distinctly Viking or Anglo-Scandinavian artefacts. The following highlights some of these finds and where they can be seen or are held. Jewry Wall Museum, Leicester Victorian chance finds from Leicester include a pendant, with an openwork writhing beast in a circular frame from Highcross St. (LA18.1860). Two beautifully carved bone objects were also recovered from there: a beast's head with gaping mouth and a ‘tongue’ shaped strap end decorated with interlace and cat-like masks (LA67.1864). Kenyon’s excavations at Jewry Wall in 1948 found an unusual mount akin to an oval brooch (JW85.1) and two ‘Norse’-type ring-headed pins (LA33.1951) with a third already recovered from Cank St. in 1912 (LA116.1962). Just outside the city at Aylestone church, a wonderful stone object was found. It's a grave cover which appears to be Scandinavian in style with ‘triskeles’ and beasts decorating its surface (LA103.1969). Unfortunately, Jewry Wall Museum is closed for renovations as this blog is posted. Charnwood Museum, Loughborough In the county, we have the rare silver Thor's hammer pendant from Thurcaston on display at Charnwood Museum (PAS ref LEIC-185125). It was found by the same person who found our only Viking coin hoard, the Thurcaston hoard (LEIC-C6D945), which is currently held at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge but is unfortunately not on display. The hammer-shaped pendant was very rare when found in 1991, but we now have 22 examples on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database, including a rare gold Thor's hammer from East Lincolnshire (LIN-D3E540) which has similar decoration to the Thurcaston one. We also have a very rare sword pommel (Peterson type X LEIC-9158C3) from Ravenstone, metal detected and donated by the finder. It features ‘Ringerike’ ribbon-like decoration, dating it to the early 11th century. This is not yet on display but will be at Charnwood Museum for a temporary display in the Spring. Melton Carnegie Museum, Melton Mowbray In Melton Museum we have objects that are Anglo-Scandinavian, including a very rare stirrup mount from Kirby Bellars (LEIC-51E6F2). The only one of its type from Britain, its only parallel being continental and in the British Museum. We also have a harness strap distributor, one of many Anglo-Scandinavian horse accessories recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Further reading Stirrup mounts - https://finds.org.uk/counties/leicestershire/a-pair-of-stirrup-strap-mounts

Read More

A Silk Headscarf from Lincoln

In the archaeology stores of The Collection in Lincoln is a very rare Viking silk headscarf found in the early 1970s. There was an excavation in advance of a development at Saltergate in Lincoln that uncovered a previously unknown Roman gateway as well as a Roman house, part of an Anglo-Saxon graveyard and in a pit, a silk headscarf about 20 centimetres wide and 60 centimetres long. The pit was found under a council office that was being demolished and the brick-lined cellar created the perfect conditions for this fragile item to survive. The pit has been dated to the tenth century, so roughly when Lincoln was an important Viking trading settlement. The name Saltergate means the street of the salt-makers or traders, gata being the Old Norse word for street. The earliest reference to Saltergate is in the thirteenth century, although the street later became Corporation Lane, and the name Saltergate was only reintroduced in 1831. Occasionally silk headscarves have survived on sites in Sweden and the Netherlands, but most have been found in the Viking towns of the British Isles (four from Dublin, three from York and this one from Lincoln). The secret of making silk was jealously guarded in the medieval period and the Byzantine Empire was the only place outside China where it was made. The weave from this scarf matches Byzantine silk suggesting it came from the eastern Mediterranean and amazingly it is so similar to one found in Coppergate in York that we think the two examples came from the same larger piece of material. Of course archaeologists from York think it was cut up there while I have a certain Lincolnshire bias, so think Lincoln imported the material and then smaller scarves were made from it and some re-exported north to Jorvik! The material is very expensive and exotic, so whoever wore it must have paid a good price for it. How the headscarf was worn is a matter of debate. Most reconstructions of such scarves have the material laid across the head with the two long seams at the back sewn together so it covers the rear of the head (and hair). There is a reconstruction on display in the Posterngate that has the silk headscarf merely as a strip of material worn sideways across the head with ties attached to the bottom front corners to keep it on the head. The original is in conservation and too fragile to put on display. How Viking women wore their hair is a matter of debate. The only written evidence is from much later Old Norse sagas that give a few clues which are hard to interpret. Representations of Viking women in stone carvings or metal figures are also tricky to understand. The figures in such carvings are often small so it is not easy to know what is a scarf, a cap or a braid of hair. We also don't know why women wore such scarves; perhaps women were expected to cover their hair for religious or cultural reasons in Viking towns. Perhaps the scarf was there as a fashion statement, to show off the wearer's wealth or maybe just a way of keeping her hair neat. The reconstruction can be seen as part of the Posterngate tours to see the Roman gateway. They only occur a few times a year, in 2019 it will probably be 1st March, 1st June and 1st of November (but it is worth checking The Collection's website prior to making a trip in case those dates or prices change) and costs approximately £2 per head to visit.