Slithering Swords in the Viking World

By Dr Sue Brunning (Curator, European Early Medieval Collections, British Museum)

Posted in: Archaeology, Vikings

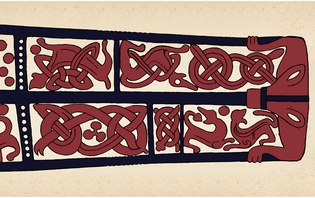

Reproduction of Viking Age sword from Repton by Adam Parsons

Forget Vikings and The Last Kingdom – the most pulsating depictions of Viking Age battle appear in early medieval Scandinavian poetry. Here, armies transform into elemental forces and fierce creatures, clashing together in a mass of noise and light. Popular in this imagery is the likening of swords to snakes, with poets styling these weapons as ‘wound snakes’ and ‘battle snakes’ that bite at their enemies.

This was not just poetic flourish. Real Viking swords also had something of the snake about them. Their pattern-welded blades writhe with sinuous designs, their hilts with looping serpents. Scale-like panels encrust the heavy hilts of Petersen’s Type D swords; one from Trælnes, Norway even has dark diamonds on a brighter background, mirroring the dark-on-light streak along an adder’s back. Similar designs were made with inlaid wire on other swords. It is even tempting to ponder whether coiled-up blades in Viking burials evoked the posture of resting snakes.

How and why did this union between swords and snakes come about? Well, both are long, thin, bulbous at one end and tapered towards the other; they are glossy with mottled markings; both shed their skin (or scabbard); they weave about and bite when threatened. This would be an elegant explanation if snakes were just ‘snakes’, shall we say; but in Viking Scandinavia, serpents held immense symbolic significance. They permeate Scandinavian cosmology, from the ‘world serpent’ Jǫrmungandr to Óðinn using a snake’s form to steal the mead of poetry. Clearly, poets did not just liken swords to snakes because they looked a bit similar. So, what was going on?

Poets often paired snakes with key symbols of power and status in the Viking world, namely arm-rings, gold and ships. Swords behaved similarly in Viking thought, so it is perhaps no surprise that snakes dominate their description and decoration. But the ambiguity surrounding snakes may also have been a factor. In Norse mythology, serpents represented both order and destruction (Jǫrmungandr binding the world together, then running rampant at Ragnarǫk). Similarly, in the poem Rígsþula Heimdallr’s highest born child has ‘piercing’ eyes ‘like a young snake’s’, but in Skirnismál the ‘shining serpent’ is ‘hateful to men’. Such contrasting feelings also applied to swords, which were instruments of order (protecting one’s self, comrades, kingdom) and chaos (destroying those of your enemy). This tension is captured by a Valkyrie in the poem Helgakviða Hjǫrvarðssonar, who knows a sword that is ‘better than all the rest’ – but it is also ‘the evil one among battle-needles’. This verse may encapsulate why swords and snakes intertwined in Viking minds: two powerful beings that were at once alluring and deadly.

References

Brunning, S., ‘”(Swinger of) the Serpent of Wounds”: Swords and Snakes in the Viking Mind’ in Representing Beasts in Early Medieval England and Scandinavia, ed. by Michael D. J. Bintley and Thomas J. T. Williams (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2015)