A Silk Headscarf from Lincoln

By Dr Erik Grigg, The Collection, Lincoln

Posted in: Archaeology, East Midlands, Viking Age

A Viking Age silk headscarf

Image (c) Erik Grigg

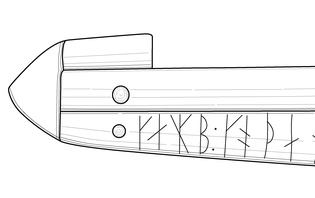

In the archaeology stores of The Collection in Lincoln is a very rare Viking silk headscarf found in the early 1970s. There was an excavation in advance of a development at Saltergate in Lincoln that uncovered a previously unknown Roman gateway as well as a Roman house, part of an Anglo-Saxon graveyard and in a pit, a silk headscarf about 20 centimetres wide and 60 centimetres long. The pit was found under a council office that was being demolished and the brick-lined cellar created the perfect conditions for this fragile item to survive. The pit has been dated to the tenth century, so roughly when Lincoln was an important Viking trading settlement. The name Saltergate means the street of the salt-makers or traders, gata being the Old Norse word for street. The earliest reference to Saltergate is in the thirteenth century, although the street later became Corporation Lane, and the name Saltergate was only reintroduced in 1831.

A reconstruction of how a headscarf could have been worn

Image (c) Erik Grigg

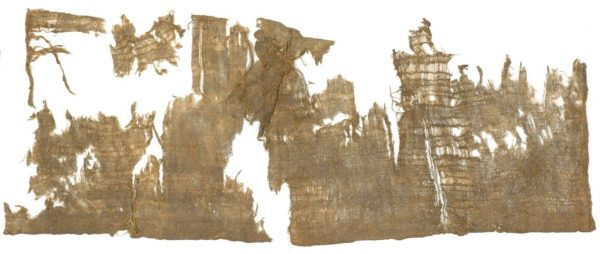

Occasionally silk headscarves have survived on sites in Sweden and the Netherlands, but most have been found in the Viking towns of the British Isles (four from Dublin, three from York and this one from Lincoln). The secret of making silk was jealously guarded in the medieval period and the Byzantine Empire was the only place outside China where it was made. The weave from this scarf matches Byzantine silk suggesting it came from the eastern Mediterranean and amazingly it is so similar to one found in Coppergate in York that we think the two examples came from the same larger piece of material. Of course archaeologists from York think it was cut up there while I have a certain Lincolnshire bias, so think Lincoln imported the material and then smaller scarves were made from it and some re-exported north to Jorvik! The material is very expensive and exotic, so whoever wore it must have paid a good price for it.

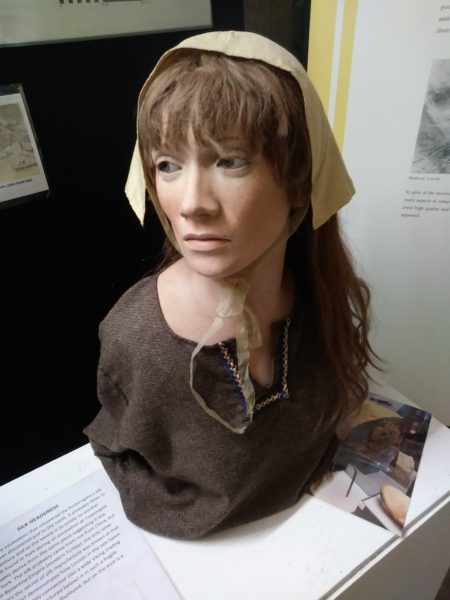

How the headscarf was worn is a matter of debate. Most reconstructions of such scarves have the material laid across the head with the two long seams at the back sewn together so it covers the rear of the head (and hair). There is a reconstruction on display in the Posterngate that has the silk headscarf merely as a strip of material worn sideways across the head with ties attached to the bottom front corners to keep it on the head. The original is in conservation and too fragile to put on display.

A reconstruction of how a headscarf could have been worn

Image (c) Erik Grigg

How Viking women wore their hair is a matter of debate. The only written evidence is from much later Old Norse sagas that give a few clues which are hard to interpret. Representations of Viking women in stone carvings or metal figures are also tricky to understand. The figures in such carvings are often small so it is not easy to know what is a scarf, a cap or a braid of hair. We also don’t know why women wore such scarves; perhaps women were expected to cover their hair for religious or cultural reasons in Viking towns. Perhaps the scarf was there as a fashion statement, to show off the wearer’s wealth or maybe just a way of keeping her hair neat.

The reconstruction can be seen as part of the Posterngate tours to see the Roman gateway. They only occur a few times a year, in 2019 it will probably be 1st March, 1st June and 1st of November (but it is worth checking The Collection’s website prior to making a trip in case those dates or prices change) and costs approximately £2 per head to visit.