The Danelaw: a place or an idea?

Professor Judith Jesch, University of Nottingham

Posted in: East Midlands, Viking Age, Vikings

Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. Photo by Judith Jesch.

The Danelaw: a place or an idea? This question was posed by Melvyn Bragg in a recent edition of In Our Time on Radio 4. The correct answer is ‘a bit of both’. But it’s a very good question and one worth a bit more exploration.

As an area, the Danelaw is often thought to have been established in the treaty made at Wedmore between King Alfred and the Viking leader Guthrum in the 880s. While only recorded in later manuscripts, it is generally accepted as a true record of what was just one of several treaties between English rulers and Viking leaders at the time. The treaty is rather specific in being between ‘King Alfred and King Guthrum and the council of all the English nation and all the people which are in East Anglia’. It defines a boundary which goes ‘up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then straight to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street’. In this way the treaty delineates the area within which the provisions of the treaty apply but does not define who is in charge there. The provisions themselves are quite basic and are to do with the relationship between Danes and English, in cases of manslaughter, the purchase of men, horses or oxen, and recruitment to either army. In all the treaty is a practical, and limited, agreement which makes no assumptions about who occupies or holds the defined territory, which is in any case quite vague about how far north it might extend. There is also no suggestion in the treaty of any difference between ‘Danish’ and ‘English’ law, in fact the treaty takes pains to assess the compensation for the manslaughter of an English or a Danish man at the same amount.

The idea that there are two legal jurisdictions, in which that of the Danes, or of Danish-held territory, is distinct from its English equivalent, does not become clear in documents until the early eleventh century. In these, lagu ‘law’, an Old Norse word introduced into Old English by Archbishop Wulfstan, collocates with the ethnonym Dena to express the idea of the ‘law of the Danes’, but the term is not yet a compound as in ‘Danelaw’. For example, in Æthelred’s law code (VI) of 1008, Wulfstan distinguishes between on Ængla lage 7 on Dena lage be þam þe heora lagu sy. This might be translated as ‘in the jurisdiction of the English and in the jurisdiction of the Danes according to what their legal practice might be’ and there are several similar uses of the term around this time. What this shows is that there is an idea of a Scandinavian (or Anglo-Scandinavian, as argued by Lesley Abrams) legal province within the English kingdom. This province is presumably territorially defined, though this is not actually indicated in the legal codes themselves.

An earlier code of Æthelred (III, from around 1002, known as the Wantage code), does not use the Danelaw term but does mention the Five Boroughs and makes extensive use of Scandinavian legal language in legislating for that region. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in a poetic entry for 942, makes a distinction between the Danes of the Five Boroughs (Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford) and the Norsemen who ruled north of them and from whose subjugation the Danes were freed by King Edmund. All this suggests that the Scandinavian legal province recognised in the law codes of the time reached only as far as the Humber, but that the legal distinctions between Danes and English were still important (and recognised) in the eleventh century, some 50-100 years after English rulers had conquered the Scandinavian-ruled areas during the tenth century.

So, ‘Danelaw’ is not a term for the area defined in the treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. Also, as a legal concept it appears only to apply to an area south of the Humber, more specifically perhaps just the region of the Five Boroughs. However neither of these is how the term is most commonly used today. Despite its origin in the law codes of the early eleventh century, today the term is most frequently used in a more general way, without necessarily any reference to law, jurisdiction or even a well-defined area. Most commonly it is used to refer to that part of England which was, for want of a better word, ‘influenced’ by the activities of Scandinavians, whether they were the so-called ‘Great Heathen Army’ of the ninth century or peaceful settlers in the tenth. It is only after King Cnut became king of all England in the eleventh century that the distinction between ‘Danish’ and ‘English’ England becomes hard to sustain. The reign of Cnut and, briefly, his son Harthacnut brought new Scandinavian incomers to England, who often reached parts of England not otherwise thought of as falling within the ‘Danelaw’ and the overall picture is quite different.

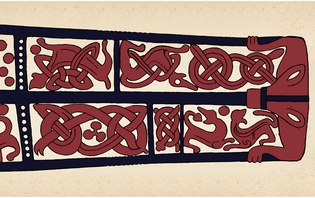

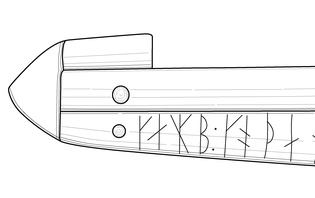

To use the term ‘Danelaw’ in this general sense is actually quite misleading. It implies that only Danes were involved in the Scandinavian impact on England, and that, whether idea or area, it is mostly about law and jurisdiction. But many scholars use the term in contexts where they are looking at the Scandinavians’ influence on settlement, culture both material and immaterial, and language, as well as their impact on church and society. Evidence for this influence and impact can be found in large parts of eastern and northern England, including regions far from the area described in the Treaty of Wedmore, or the Five Boroughs. Areas in the north-west, such as Cumbria, have plentiful evidence of Scandinavian influence in burials, metalwork, place-names, dialect, sculpture and runic inscriptions, yet there is almost no documentary evidence for how this Scandinavian influence came about. Is Cumbria part of the Danelaw? It was certainly part of the great Viking diaspora that affected much of England from the ninth to the eleventh (or even twelfth) century, yet the term ‘Danelaw’ does not seem entirely appropriate to describe that region in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

Perhaps it is best to use the term ‘Scandinavian England’ (as in the title of an important collection of essays by F. T. Wainwright). Even better would be ‘Anglo-Scandinavian England’, since even the areas most heavily influenced by the Scandinavian incomers never completely lost their Anglo-Saxon inhabitants, material culture, customs or language. But although the term ‘Danelaw’ is inadequate, we should not completely forget it either. At the very least it reminds us that those supposedly lawless Vikings actually gave the English language its word for ‘law’, as still used today.

References:

Lesley Abrams, ‘Edward the Elder’s Danelaw’, in Edward the Elder 899-924, ed. N. J. Higham and D. H. Hill. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 128-43.

Lesley Abrams, ‘King Edgar and the men of the Danelaw’, in Edgar, King of the English 959-975, ed. Donald Scragg. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008, pp. 171-91.

Katherine Holman, ‘Defining the Danelaw’, in Vikings and the Danelaw, ed. James Graham-Campbell et al. Oxford: Oxbow, 2001, pp. 1-11.

Sara M. Pons-Sanz, Norse-Derived Vocabulary in Late Old English Texts, Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, 2007, pp. 70-72.

Simon Trafford, ‘The Alfred-Guthrum treaty’, in Cultures in Contact. Scandinavian settlement in England in the ninth and tenth centuries, ed. Dawn M. Hadley and Julian D. Richards. Turnhout: Brepols, 2000, pp. 43-64.

F. T. Wainwright, Scandinavian England, London: Phillimore, 1975.

Dorothy Whitelock, English Historical Documents I. c. 500-1042. London: Routledge, 1996 [2nd ed.].

Early English Laws http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/