In this area we present our blog posts on a variety of Viking subjects from a variety of authors. Please scroll down or use the filter to look at specific subjects…

Explore our blog posts...

Viking Art Styles in the East Midlands: Borre

Traders, raiders, and artists? When Vikings are conjured in the popular imagination they clasp swords rather than chisels, but many of the Viking Age objects found in the East Midlands demonstrate intricate craftsmanship that still survives after a thousand years. Scandinavian art styles evolved throughout the Viking Age (c. 800-1100 AD) and are today classified into a loose chronology: Borre, Jelling, Mammen, Ringerike, and Urnes. These styles often overlap stylistically and chronologically, but there are enough distinctive features and recurring motifs to separate objects in various media into these identifiable styles. These art styles further developed in the British Isles with some objects retaining pure 'Viking' ornament or featuring a hybrid Insular style that slightly modifies Scandinavian features to fit a new social and artistic context. This blog series will briefly explore the characteristics of the Scandinavian art styles appearing in the East Midlands through the objects themselves. The Borre Style One of the earliest Viking art styles, the Borre style, was prevalent in Scandinavia from the the late ninth to the late tenth century. The style derives its name from group of bronze harness mounts discovered in a ship grave from Borre, Vestfold, Norway. The style is characterised by a range of geometric and zoomorphic motifs and the occasional gripping beast. The Borre Style in the East Midlands The Borre style came to England with the Scandinavian settlers from the late ninth century. The style proved to be popular amongst insular artists and appears on several forms of media such as stone sculpture and metal brooches throughout the British Isles. One object in the East Midlands that exemplifies the Borre style is a gilded, copper alloy equal armed-brooch fragment found in Harworth Bircotes, Nottinghamshire. There is a diagnostic Borre style beast with gripping arms and legs that has parallels with a find in Birka, Sweden. However, the gripping beast motif in England is quite rare as this brooch fragment is one of only six Scandinavian, Viking period equal-armed brooches recorded in England. Another copper alloy, gilded disc brooch in the Borre style found in Cossington, Leicestershire was probably brought to England from Denmark. The interweaving tendrils on this disc are characteristic of the Borre style and recall interlacing loops formed from gripping beasts. Scandinavian brooches tended to be domed with a hollow back compared to the English counterparts which were flat at the time. The Borre style is not restricted to brooches in the East Midlands, it is also found on other objects such as this copper-alloy strap-end found in Brookenby, Nottinghamshire. The style is also found on a few buckles in the East Midlands including the copper-alloy belt fragment pictured below which is thought to be from a flat buckle. The object was found near Coddington, Nottinghamshire, and has few comparable examples. Another copper-alloy buckle was found near Earl Shilton, Leistershire. This buckle consists of an oval loop with a circular cross section and has an elongated triangular pin rest in the form of an animal head. The animal head has a pointed snout, rounded head with rounded upwards pointing ears which merge into the buckle loop. All of these artefacts display the variety of isomorphic and geometric designs found within the Borre style and how this style was used to decorate different kinds of objects. The Ring Chain An instantly recognisable motif of the Borre style is the symmetrical, double contoured ring-chain. 'This composition consists of a chain of interlacing circles, divided by transverse bars and overlaid by lozenges' (Kershaw 2010, 2). Occasionally, the ring-chain terminates in an animal. The ring-chain appears in a modified 'vertebral' variant on stone sculptures in the British Isles where 'a rib of truncated triangles' is 'flanked by side loops' (Kershaw 2010, 2). The best-known example of the vertebral ring-chain is on the Gosforth Cross in Cumbria, but it is also found in the Isle of Man, Yorkshire, and even the East Midlands, engraved on a stone from St. Mary's Church in Bakewell, Derbyshire. References: Kershaw, Jane 2010. 'Viking-Age Scandinavian art styles and their appearance in the British Isles Part 1: Early Viking-Age art styles', Finds Research Group Datasheet 42, pp. 1-7

Read More

The Rich and the Brave: Burials, Weapons, and Warriors

The common association of highly furnished weapon burials containing a male skeleton with warriors is still a highly debated topic and one that has a profound impact on how we view Vikings. Much scholarly ink has been spilled discussing theories surrounding motivations behind grave good deposition and the relation between weapon burials and the deceased in Scandinavia, Britain, and with varying degrees of success. Choosing which theory to apply to a situation is complicated by a variety of factors not least of which is that historical, geographical and chronological context changes how one interprets a ritual depending on the time and place it was practised. Furthermore, there is usually no knowledge of who selected the objects to be deposited and thus no concrete idea why they did so. According to Heinrich Härke, textual sources are the best means with which to attempt to determine motivations but are rarely present for the space and time under review (Härke 2014, 53–54). While weapons are highly-visible in archaeological contexts, their use in burials only represents a small segment of the population within a social context that had many different high-status burial practices (Harrison 2015, 314). Secondly, poorly furnished burials are understudied with no definitive comments made about them (Harrison 2015, 314–15; 2008, 166–90). In addition, the relationship between perceived and actual status and the fact that no artefact has a fixed value or meaning but rather its meaning is imposed both complicate the issue further (Harrison 2015, 304). The perceived importance of an individual is heavily influenced by local burial tradition. For example, at Kilmainham/Islandbridge a large number of weapon burials with high-quality swords were discovered which reflects the importance of Dublin between the ninth and tenth centuries while the number of graves containing these high-quality swords may reflect the role competitive display played within Dublin society (Harrison 2015, 304; Harrison and Ó Floinn 2014, 75–93). However, the situation in the former Danelaw is very much the opposite with a general paucity of weapon burials east of the Pennines (Harrison 2015, 304; Graham-Campbell 1980, 379; Richards 2000, 142). Harrison argues that this may be a reflection of the higher value placed on weapons in the Danelaw than in Dublin or elsewhere along the western seaboard (Harrison 2015, 304). One last point to consider when examining burials and grave goods is that the choice of grave goods can reflect how the deceased or those burying them wished their identity to be portrayed can equally affect weapon burials. Moreover, grave goods can underline the hybridity of an individual’s identity. For example, the shield bosses of Kilmainham/Islandbridge combine elements of both Irish small bosses and Anglo-Saxon conical bosses to create a fusion shield boss type only found near Dublin reflecting the distinct local identity of its elites (Harrison 2015, 309; Harrison and Ó Floinn 2014, 122–25; Bøe 1940, 33, 38). So how can weapons in burials be used to potentially identify whether or not individuals were involved in military activities? In simple terms, there is no definitive way of correlating the two but by studying the graves within their historical and geographical context, it may be possible to make a case. One strong indicator that an individual may have been involved in military activities are any signs of trauma on the skeletons, such as those found at Repton, alongside the inclusion of weapons as grave-goods. References: Bøe, Johs. 1940. Viking Antiquities in Great Britain and Ireland, Part 3: Norse Antiquities in Ireland. Edited by Haakon Shetelig. Oslo: H. Aschehoug. Graham-Campbell, James. 1980. ‘The Scandinavian Viking-Age Burials of England: Some Problems of Interpretation’. In Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries, edited by Phillip Rahtz, Lorna Watts, and Tania Dickinson, 379–82. British Archaeological Reports British Series 82. Oxford: Archaeopress. Härke, Heinrich. 2014. ‘Grave Goods in Early Medieval Burials: Messages and Meanings’. Morality 19 (1): 41–60. Harrison, Stephen. 2008. ‘Furnished Insular Scandinavian Burial: Artefacts & Landscape in the Early Viking Age’. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin. Harrison, Stephen. 2015. ‘“Warrior Graves”? The Weapon Burial Rite in Viking Age Britain and Ireland’. In Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World, edited by James Barrett and Sarah Gibbon, 299–319. Society for Medieval Archaeology. Leeds: Maney Publishing. Harrison, Stephen, and Raghnall Ó Floinn. 2014. Viking Graves and Grave-Goods in Ireland. Dublin: National Museum of Ireland. Richards, Julian. 2000. Viking Age England. Stroud: Tempus.

Read More

Winter Camps in the East Midlands: Commerce and Industry

Viking winter camps were more than just bases for the Great Army to live in during the winter or centres from which armed Viking bands could conduct military activities. From their inception winter camps established and maintained economic functions whether as centres for trade or industry. Both Repton and Torksey were placed in a location that allowed them to take advantage of the River Trent as a means of transportation of people and goods. Repton’s evidence for trading activities is not as abundant at Torksey but finds of lead weights as well as Anglo-Saxon and Frankish coins point towards commercial activities. Evidence of industrial activities at the site includes several ship nails, include slag, woodworking tools, the tip of a Viking axe head, an area for metal working, and another area with signs of butchering of animals (Jarman 2018a, 33–34; 2018b, 20–21; Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 72). The nails and, perhaps, the woodworking tools could be taken as evidence for ship repair. It is also to keep in mind that the nature of extended occupation, the likelihood of camp followers, especially women, as well as the need for animals and supplies further evidences non-military activities and a larger occupation area than the fortified enclosure (Raffield 2016, 15, 21). Archaeological excavations of Torksey have uncovered quite a few pieces of bullion, including hacksilver and jewellery (Raffield 2016, 313, 319; Hadley and Richards 2016, 27; Blackburn, Williams, and Graham-Campbell 2007, 71–72; Williams 2007, 183; McLeod 2014, 122–23). The relatively high concentration of gold at Torksey suggests that it was being used in transactions and not just as a status symbol which may explain the presence of hack-gold, ingots, and gold plated copper coins (Hadley and Richards 2016, 47; Blackburn, Williams, and Graham-Campbell 2007, 75–77; Blackburn 2011, 233–34). A large abundance of lead weights were also found, which are associated with merchants, with 15 resembling Scandinavian/Islamic weights from Sweden (Hadley and Richards 2016, 48; McLeod 2014, 159). Over 350 coins were also found on the site including English silver pennies, stycas from Northumbria, an imitation Frankish solidi of Louis the Pious, and 124 Arab dirhams (Hadley and Richards 2016, 43; Blackburn 2011, 225). The Arabic coins further prove just how connected the site would have been to the wider Scandinavian trade network even during the army’s years of campaigning. A variety of overwintering activities would have occurred at Torksey. Alongside iron clench nails, a hoard of iron woodworking nails have been discovered making it likely that Torksey would have been ideal for the repair of ships (Hadley and Richards 2016, 53–54). Additionally, worn and damaged tools were located alongside fragments of iron vessels seemingly ready to be reworked (Hadley and Richards 2016, 53). Furthermore, the discovery of spindle whorls, needles, punches and awls suggest textile-working, a job generally undertaken by women and thus providing potential evidence for a female presence at the camp (Hadley and Richards 2016, 54). These finds also suggest that overwintering activities such as the repair of sails, tents and clothing took place. Along with trading goods plundered from their campaigns, the Great Army also employed craftsmen to manufacture pottery as a tradable commodity. Evidence of pottery production at Torksey was first ascertained by excavations south of the modern village in 1949 (Perry 2016, 74). The spread of so-called ‘Torksey ware’ was vast and it even became the major pottery type at York to the point where archaeologists first assumed that it was locally made (Perry 2016, 76). Biddle, Martin, and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle. ‘Repton and the “Great Heathen Army”, 873–4’. In Vikings and the Danelaw: Select Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress, edited by James Graham-Campbell, Richard Hall, Judith Jesch, and David Parsons, 45–96. (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2001). Graham-Campbell, James, and Gareth Williams. Silver economy in the Viking Age. (Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, 2007). Hadley, Dawn M., and Julian D. Richards. "The winter camp of the Viking Great Army, AD 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire." The Antiquaries Journal 96 (2016): 23-67. Jarman, C. "Resolving Repton: has archaeology found the great Viking camp." British Archaeology (2018): 28-35. Jarman, Catrine L., Martin Biddle, Tom Higham, and Christopher Bronk Ramsey. "The Viking Great Army in England: new dates from the Repton charnel." antiquity 92, no. 361 (2018): 183-199. McLeod, Shane. The Beginning of Scandinavian Settlement in England The Viking'Great Army'and Early Settlers, c. 865-900. (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014). Perry, Gareth J. "Pottery production in Anglo-Scandinavian Torksey (Lincolnshire): reconstructing and contextualising the chaîne opératoire." Medieval Archaeology 60, no. 1 (2016): 72-114. Raffield, Ben. "Bands of brothers: A re‐appraisal of the Viking Great Army and its implications for the Scandinavian colonization of England." Early Medieval Europe 24, no. 3 (2016): 308-337.

Read More

Winter Camps in the East Midlands: Location and Layout

Our knowledge of the Viking Great Army's movments during its campaigns in England is provided by entries in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a compilation of annalistic entries that describe events in a particular year. Despite some drawbacks to using the chronicle as a source, it does provide a roadmap for where the Vikings stopped for the winter. In fact, these were termed wintersetl by the compilers of the chronicle otherwise known as winter camps. Two of the winter camps mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are under current investigation, Repton and Torksey. Both winter camps are located along a river which would have provided the Viking inhabitants with vital transportation links required in most raiding or trading activities. It would also seem likely that the waterways were selected in order to provide a natural defensive element to the settlement, usually alongside another natural feature such as a raised promontory or a marsh, or an easy means of escape if the settlement was overwhelmed. In addition, the winter camps seem to be placed in relation to recently captured territory which makes sense for force out on campaign. Viking invaders took Repton and immediately constructed a D-shaped wall using the pre-existing church as a gatehouse. The remnants of this wall were discovered in the 1970s and 1980s in the form of a V-shaped ditch, calculated to have been about 8m wide and 4m deep, cutting through the earlier Anglo-Saxon monastic burials (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 57, 59; Jarman 2018a, 29). The 1979 excavations revealed four successive ditches; the V-shaped ditch with a flat narrow bottom was the earliest and was backfilled shortly after being dug (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 58). The ditches have been dated to between the Group 2 Middle Anglo-Saxon and Group 3 Post-Viking burials, which fits with late ninth-century ‘Great Army’ occupation (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001, 59). Unlike Repton, in Torksey Vikings only utilized natural defences, such as the river Trent and the wet marshy ground, which turned the settlement into an island (Hadley and Richards 2016, 32; Raffield 2016, 313). Despite not having any walls or ditches, it is likely that the ‘Great Army’ would have found the water and marsh defence sufficient in light of their recent peace with Mercia (Raffield 2016, 323). In terms of buildings there is a general lack of evidence for permanent structures at both Torksey and Repton. It is unclear whether this is due to poor preservation, need for more archaeological investigation, or that they truly did not exist. The use of Repton, Torksey, and the other wintersetl as army bases during campaigning probably explains the lack of permanent dwellings and workshops from their foundation but does not explain why none were built throughout the rest of their occupation when the army left. The lack of urban planning and systems of streets and plots likely has to do with either a lack of refinement in terms of the methodology and ideas behind settlement foundation which requires more experience over time, the motivations and needs surrounding the foundation of a settlement, or even a combination of both. As mentioned above, the wintersetl in England were created, primarily, to house a military force on campaign, which moved on very quickly after the settlement was established. Therefore, it would not make sense to spend time and resources developing a systematic layout nor to begin the time-consuming process of building permanent structures. References: Biddle, Martin, and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle. 2001. ‘Repton and the “Great Heathen Army”, 873–4’. In Vikings and the Danelaw: Select Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress, edited by James Graham-Campbell, Richard Hall, Judith Jesch, and David Parsons, 45–96. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Hadley, Dawn, and Julian Richards. 2016. ‘The Viking Winter Camp and Anglo-Scandinavian Town at Torksey, Lincolnshire – the Landscape Context’. The Antiquaries Journal, no. 96: 23–67. Raffield, Ben. 2016. ‘Bands of Brothers: A Re-Appraisal of the Viking Great Army and Its Implications for the Scandinavian Colonization of England’. Early Medieval Europe 24 (3): 308–37.

Read More

Brooches, Pendants and Pins: Scandinavian Dress Accessories in England

Nowadays it is common to see people wearing various accoutrements such as earrings, necklaces, pendants, or rings. The Viking Age was no different and Scandinavian fashion, both female and male, commonly featured the use of dress accessories which served a practical purpose of fastening clothing but also as a way to display wealth and status. Below is a brief discussion on the use and place of Scandinavian brooches, pendants and pins in England. Brooches were a typical part of female dress. Scandinavian brooches came in a variety of sizes and shapes which included disc, trefoil, lozenge, equal-armed, and oval shapes. The different brooch types served a variety of functions in Scandinavian female dress with oval brooches typically being used as shoulder clasps for apron-type dresses and the rest being used to secure an outer garment to an inner shift. Anglo-Saxon brooches do not match this diversity of form with large disc brooches being typical of ninth-century dress styles with smaller ones becoming more popular in the later ninth and tenth centuries. However, since disc brooches were used by both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian women they are distinguished by their morphology. Scandinavian brooches were typically domed with a hollow back while Anglo-Saxon brooches were usually flat. Moreover, Anglo-Saxon brooches were worn singly without accompanying accessories. With some exceptions, pendants were generally worn by women as an accessory to Scandinavian dress. Pendants were a popular dress accessory in Norway and Sweden and sometimes were worn with beads between a pair of oval brooches. However, in England, pendants did not have the same popularity among Anglo-Saxon inhabitants. An unique style of pendant the existence of which was likely influenced by crucifixes worn by Christian individuals was the Thor’s Hammer pendant. These may have been worn to show devotion to the god Thor, or to secure the god’s protection, although there is little evidence to support this interpretation. Pendants like this have been found made of lead, copper alloy, silver and gold, showing that many different strata of society could have worn them. Pins were another form of popular dress accessory, though tending to be more practical , and mostly used for fastening cloaks. Once such pin, the ringed pin, was a form of dress fastener which developed as a result of contact between artisans in the Celtic West and sub-Roman Britain. The type became very popular in Ireland, being ultimately adopted by the Hiberno-Norse during the Viking period. In form it comprised a pin with a ring inserted through a looped, perforated or pierced head. Another style of pin has a solid head, round or cuboid, with ring-and-dot pattern ornamentation. These were common in Ireland and the western British Isles, and spread further afield under Viking influence. Kershaw, Jane F. Viking Identities: Scandinavian jewellery in England. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 20-25

Read More

Two Languages, One Name: Hybrid Place-Names in the East Midlands

Resting in the Trent river valley are the small villages of Gonalston, Thurgarton, and Rolleston. You are politely asked 'Please slow down', whilst you drive through, but don't be fooled by the signs because Vikings lie in wait. Gonalston 'Gunnolfr's farm/settlement', Thurgarton ' Þorgeirr's farm/settlement', and Rolleston 'Hróaldr's farm/settlement' all belong to a group formerly called Grimston-hybrids where the first element of the place-name is a Scandinavian personal name and the second element of the name is Old English tūn 'an enclosure; a farmstead; a village; an estate'. These names were called Grimston-hybrids because the largest single group of these types of names consisted of places named Grimston 'Grim's village, estate'. However, not all Grimstons fit within a certain pattern and not all Grims are derived from from Old Norse. Therefore, the late Kenneth Cameron, formerly professor at the University of Nottingham, suggested that place-names with a Scandinavian personal name and Old English tūn be called Toton-hybrids. The name comes from Toton, Nottinghamshire, an Anglo-Scandinavian compound from the Old Norse male personal name Tófi and the Old English element tūn ‘farm, settlement’. There is continued discussion on the distribution of Toton-hybrids and why they exist, but it is likely that the personal names represent landowners, either Scandinavians granted land in the initial stages of conquest, or individuals with Old Norse names in the decades following. Alternatively, it is possible that these were formerly Old English place-names replaced and renamed by the Vikings. Another suggestion has been that the Vikings borrowed Old English tūn to use in new names because tūn's Old Norse equivalent, tún, is sometimes used in Scandinavian place-names, but is very rare in England (Gregory 2017, 60). Not all Anglo-Scandinavian compounds are Toton-hybrids, and some place-names appear to be simply the result of the combination of two languages. Sookholme, Nottinghamshire, for example, comes from Old English sulh 'a plough; a ploughland' and Old Norse holmr 'an island, an inland promontory, raised ground in marsh, a river-meadow'. Also, in Nottinghamshire is Eastwood which comes from Old English east 'east' and Old Norse þveit 'a clearing, a meadow, a paddock'. Names of this type often indicate that an Old Norse word has become naturalised as part of the English dialect used in the region. Many other mixed-language place-names are part of the landscape of the East Midlands, perhaps one is just waiting around the corner. Rebecca Gregory, Viking Nottinghamshire. Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications, 2017. Kenneth Cameron, English Place-Names. London: B T Batsford Ltd, 1996.

Read More

Labels and Identities in the Viking Age East Midlands II: People

For part I of this post CLICK HERE Peoples, languages and cultures The Viking Age is clearly named after the Vikings, but who were they? Much scholarly ink has been spilled on what the word means and how best to use it. For a brief summary, see this separate blog post. On this website, we use the word as is common in contemporary academic usage for people of Scandinavian origin or with Scandinavian connections who were active in trading and settlement as well as piracy and raiding, both within and outside Scandinavia in the period 750-1100. The Viking Age was a large and complex phenomenon which went far beyond the purely military, and also absorbed people who were not originally of Scandinavian ethnicity. The word is thus inclusive of people of different origins and lifestyles, and speaking a variety of languages (many were of course multilingual), but they always have some kind of Scandinavian connection. Similarly, we use the term Anglo-Saxon as a general term to refer to the people and communities who were the dominant culture in what is roughly the area of the modern country of England when the Vikings arrived, at a time before England existed. It is precisely the interactions of these two groups, the Vikings and the Anglo-Saxons, that this website explores and the terms make a useful distinction between the two groups, between whom there were otherwise many similarities: their languages were closely related and they had some aspects of their culture in common. One important difference between the two groups is that, at the time of the arrival of the Vikings, the Anglo-Saxons were thoroughly Christian, whereas the Vikings were not. However, as time went on, one of the changes that they underwent after migrating to England was a gradual conversion to Christianity, and this process can be observed in quite a lot of the evidence we present here. We are aware that arguments have been made recently that the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ is inappropriate because it has in modern times acquired racist connotations. We deplore any racist or white supremacist appropriations of the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’, or indeed ‘Viking’, and stress that we use these terms here as modern descriptors of historical phenomena and to make a useful distinction which cannot otherwise be made without further anachronism. Both of these descriptors refer to cultures that were multi-ethnic and multi-lingual, and which were well-connected to the rest of the world. However, there were distinct differences between them which were recognised at the time and which we must also recognise. The umbrella terms ‘Anglo-Saxon’ and ‘Viking’ seem to us sufficiently general and the most useful to help us understand these differences, but where more precise terms are appropriate, we use them. The everyday language of the overall group we call Anglo-Saxons is normally called Old English, which is an umbrella term for a variety of mutually comprehensible dialects. Old English is a member of the Germanic family of languages which includes the languages that later developed into German and Dutch, as well as English. The Germanic family also includes those languages that became Danish, Faroese, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish. In the Viking Age, there was little difference between these languages, and they are generally referred to as Old Norse, though sometimes we also use the term Scandinavian to distinguish them as a group from other languages. As well as surviving in place-names, this Scandinavian language also had a substantial influence on the English language as it developed into Middle and Modern English. Many words common in Present-Day English are derived from the Scandinavian language and were borrowed during the Viking Age. In discussing both the material culture and the linguistic evidence on this website, we also use terms like Anglo-Scandinavian which is intended to suggest the kind of hybrid phenomena that evolved as a result of contacts between the two groups of peoples. We also use the term Viking for certain kinds of evidence which are characteristic of the Viking Age but perhaps not obviously Scandinavian. As the Vikings travelled and migrated, they often developed new cultural forms which are not evidenced in the Scandinavian homelands (a good example being the grave markers known as ‘hogbacks’) but are still clearly associated with them. Occasionally, if evidence such as an artefact or a name is particularly associated with one of the modern Scandinavian countries, we will label it as Danish, Norwegian or Swedish, and if it is obviously Scandinavian but not restricted to one region we will use that term. We also use labels like Arabic or Frankish for objects that originated in those parts of the world, but which reached the East Midlands as a result of Viking activity. Groups, individuals and identities As today, people in the past had complex identities. Distinctions were made on the basis of gender, age and social status. People might also be identified according to a place or group of people or kin group to which they were connected, or on the basis of their religion, their role in society or their political allegiance. Nations as we know them today (England, Norway, etc.) were only just emerging in the early medieval period, so people were not commonly identified with these rather abstract entities, but they nevertheless had a good sense of geography and where people came from on a smaller scale. Many people were multilingual, but identities were also closely associated with their first or main language. Personal names might be indicators of someone’s linguistic and cultural identity, but such names can be misleading as some of them became popular across these boundaries. All of these complexities are hard to capture in the rather simplistic terms we have outlined above, but then we also know very little about how people thought about these things then. And finally, it is important to remember that people in the past were as varied as they are today. Individuals might follow the group in some things and not in others, and the groups were in any case constantly shifting. All we can do is see what patterns emerge from the evidence and generalise from those, which is what we have done with the terminology we use here, for the period when what we today call England emerged from this complex mix of peoples, cultures and languages.

Read More

Labels and Identities in the Viking Age East Midlands I: Place and Time

This website explores a period in the history of the islands of Britain and Ireland which was characterised by contact with, incursions by, and then the settlement of, groups of people whose origins were ultimately in what are today the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. We delight in showing some of the objects that these immigrants brought with them, as well as objects which were made here but to their taste or showing their influence on style and function. Other objects help us to track the places they visited and settled in, as does the less tangible evidence of language. The speech of the incomers is reflected in a wide range of names of the places the incomers settled in and which they named or renamed, or the personal names of individuals which are sometimes incorporated into those place-names. Some of this speech also survives in the present-day English language. All of this evidence not only records this early medieval episode of immigration, but most of it also demonstrates the ultimate integration of the incomers into the local community and in many cases the development of a hybrid culture. Yet other evidence in the form of stories and poems shows how communities of later periods looked back on this time which was no doubt fraught with both anxiety about change and excitement about new opportunities. Defining these groups and communities, and thus the subject of this website, is in many ways tricky, but the attempt to do so can be very illuminating. Finding the right words to explain and explore these topics is in itself a part of the process of understanding the evidence and working out what was happening back then. These words and definitions may involve some terms that were known and used at the time, but most of the terms we use were devised in more recent times as part of this process of understanding. Some of the terms are quite vague and therefore inclusive but not very precise, others are more precise but could be wrong, as there is still much we do not know. This blog attempts to set out what we mean by the terms that we use on this website, while recognising that all of them could be defined somewhat differently, or that in some cases alternative terms might be better. East Midlands Our definition of the East Midlands is not exactly that as used in 21st-century Britain, but is rather based on the concept of the Five Boroughs. This was an area under the political control of the incomers as recorded in an Old English poem concerning events in 942, which names the Five Boroughs as Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford. Four of these later became the county towns of the historical counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, which emerged as administrative divisions in the medieval period. This website is largely focused on these four counties, though with occasional glances both to neighbouring counties and to places further afield. Some county boundaries were reorganised in more modern times and we try to indicate this where relevant to help our readers orient themselves. Danelaw However we define the East Midlands, they are a part of an area known to scholars as the Danelaw, though what exactly they mean by it varies quite a lot. This term has been discussed in a separate blog post. It is used here in the general sense of ‘that part of England which was influenced by the activities of Scandinavians, whether they were the so-called ‘Great Heathen Army’ of the ninth century or peaceful settlers in the tenth’. The nature and extent of this ‘influence’ varied and that is precisely one of the things we explore in this virtual museum and our blogs. Viking Age Our chronological focus is on what we call the Viking Age, a period defined by the impact of the migrations of people of Scandinavian origin to other parts of the world. Scholars disagree over the exact dates to assign to this period, not least because there is variation in the evidence for this impact both chronologically and geographically. It seems easiest to operate with an inclusive date range and there is some consensus for a generous definition of the Viking Age as 750-1100. Since the events of the Viking Age had in some cases long-lasting ramifications, some scholars also operate with a concept of the ‘long, broad Viking Age’ which extends until about 1500. This is useful when considering high medieval evidence such as the Icelandic sagas, or an English poem such as Havelok the Dane, which shed light on the Viking Age, even though they were composed in a later period. Such cultural phenomena reflect what some have called the ‘Viking diaspora’, a term which helps to explain the world created by the migrations of the Viking Age proper. The concept of diaspora draws attention to the continuing connections migrants have with their homelands and with migrants of the same origin in other regions, as well as their interactions with the peoples they encountered when migrating. This will be explained in more detail in a future blog post. This blog post has outlined the times and places this website is mainly concerned with. A second blog post looks more closely at how we identify groups of people who lived in those times and places.

Read More

Thorfast the Comb Maker

by Erik Grigg (with the help of Janine, Paige, Josh and Hannah!) In the Viking section of the museum of The Collection in Lincoln there is a reconstruction of a Viking comb maker's workshop. The comb maker is called Thorfast by the museum staff. This is because in 1867 a comb case was found in Lincoln with a runic inscription on it that reads 'Thorfast made a good comb'. This case is now in the British Museum (though it has been out on loan a few times). The learning team decided the area and the comb maker in particular needed a makeover: the display needed a good clean, some of the items had become damaged in the eleven years he has stood there and a few items in the display were rather dated. His costume consisted of a very long tunic that was later medieval in style and very thin with no footwear so we also chose him a new outfit. Now he leans nonchalantly proud of his new gear. On the shelves is his lunch (an apple and some Viking flat bread) as well as replica cooking pots and Stamford ware. When asked about his new look he just said "Thorfast made a good comb!"

Read More

What Does the Word ‘Viking’ Really Mean?

Late Viking Age Swedish rune-stone commemorating a man called Víkingr. Swedish National Heritage Board, Photo Bengt A. Lundberg, CC BY Judith Jesch, University of Nottingham We all know about the Vikings. Those hairy warriors from Scandinavia who raided and pillaged, and slashed and burned their way across Europe, leaving behind fear and destruction, but also their genes, and some good stories about Thor and Odin. The stereotypes about Vikings can partly be blamed on Hollywood, or the History Channel. But there is also a stereotype hidden in the word “Viking”. Respectable books and websites will confidently tell you that the Old Norse word “Viking” means “pirate” or “raider”, but is this the case? What does the word really mean, and how should we use it? There are actually two, or even three, different words that such explanations could refer to. “Viking” in present-day English can be used as a noun (“a Viking”) or an adjective (“a Viking raid”). Ultimately, it derives from a word in Old Norse, but not directly. The English word “Viking” was revived in the 19th century (an early adopter was Sir Walter Scott) and borrowed from the Scandinavian languages of that time. In Old Norse, there are two words, both nouns: a víkingr is a person, while víking is an activity. Although the English word is ultimately linked to the Old Norse words, they should not be assumed to have the same meanings. Víkingr and Víking The etymology of víkingr and víking is hotly debated by scholars, but needn’t detain us because etymology only tells us what the word originally meant when coined, and not necessarily how it was used or what it means now. We don’t know what víkingr and víking meant before the Viking Age (roughly 750-1100AD), but in that period there is evidence of its use by Scandinavians speaking Old Norse. Vikings came from a world of good stories. Shutterstock The laconic but contemporary evidence of runic inscriptions and skaldic verse (Viking Age praise poetry) provides some clues. A víkingr was someone who went on expeditions, usually abroad, usually by sea, and usually in a group with other víkingar (the plural). Víkingr did not imply any particular ethnicity and it was a fairly neutral term, which could be used of one’s own group or another group. The activity of víking is not specified further, either. It could certainly include raiding, but was not restricted to that. A pejorative meaning of the word began to develop in the Viking Age, but is clearest in the medieval Icelandic sagas, written two or three centuries later – in the 1300s and 1400s. In them, víkingar were generally ill-intentioned, piratical predators, in the waters around Scandinavia, the Baltic and the British Isles, who needed to be suppressed by Scandinavian kings and other saga heroes. The Icelandic sagas went on to have an enormous influence on our perceptions of what came to be called the Viking Age, and “Viking” in present-day English is influenced by this pejorative and restricted meaning. How to use it The debate between those who would see the Vikings primarily as predatory warriors and those who draw attention to their more constructive activities in exploration, trade and settlement, then, largely boils down to how we understand and use the word Viking. Restricting it to those who raided and pillaged outside Scandinavia merely perpetuates the pejorative meaning and marks out the Scandinavians as uniquely violent in what was in fact a universally violent world. A more inclusive meaning acknowledges that raiding and pillaging were just one aspect of the Viking Age, with the mobile Vikings central to the expansive, complex and multicultural activities of the time. In the academic world, “Viking” is used for people of Scandinavian origin or with Scandinavian connections who were active in trading and settlement as well as piracy and raiding, both within and outside Scandinavia in the period 750-1100. The Viking Age was a large and complex phenomenon which went far beyond the purely military, and also absorbed people who were not originally of Scandinavian ethnicity. As a result, the English word has usefully expanded and developed to give a name to this phenomenon and its Age, and that is how we should use it, without regard either to its etymology, or to its narrower meanings in the distant past. Judith Jesch, Professor of Viking Studies, University of Nottingham This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read More

Everyday Writing in Runes in Lincoln

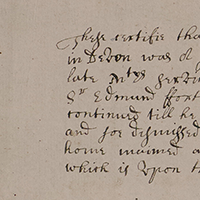

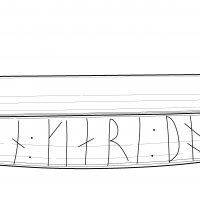

Lincoln, in the first half of the tenth century: a time of intense political, social, and economic upheaval, with the English kings of Wessex battling to regain control of one of the last strongholds of Scandinavian power in eastern England. The late ninth century had seen the ‘Great Army’ of Vikings, which had arrived in England in 865, switch its energies from raiding to permanent settlement, the start of a process of colonisation that left a lasting imprint on the street-names of Lincoln and the place-names in the surrounding countryside. As the English gradually regained control of parts of the southern Danelaw in the early tenth century, drawing ever closer to Lincoln, the town’s Viking leaders looked to the North and the support of the powerful Norse dynasty established in York by Olaf Guthfrithson, who also ruled Dublin in the west. In the lower city, close to Brayford Pool and the River Witham, lie the halls and houses of the craftsmen and merchants who had followed in the wake of the first Scandinavian settlers, turning the town into an important and prosperous trading centre. In one of these houses, we might imagine a man, sitting next to the warm hearth, eating. Hungrily he strips all the flesh from the cattle ribs and, when finished, picks up his knife and starts cutting into the smooth, flat surface of one of the ribs, listening idly to the story that his brother is telling to the children, occasionally staring into the flames of the fire. As he listens, drinking ale from his leather cup, he fills the surface of the rib with the runic letters that had been taught to him by one of the men he’d worked alongside in Norway Less well known than the rune-inscribed comb-case also found in the city, this fragmentary inscription on a cattle rib – found in disturbed deposits in St Benedict’s Square, Lincoln – doesn’t contain a clear message that can be understood today. The rib is about 10 cm long and 3 cm wide at its maximum extent. It is fragmentary, missing its top half before the first word divider in the inscription, as well as the end of rib and possibly, therefore, the end of the inscription. The runes are inscribed from left to right along the length of the rib and say: (b) - - - - - l x h i t i r x s t i n x As can be seen from the photograph above, the tops of the first few runes are missing because the bone is broken there. The brackets around the first rune indicate that the rune is incomplete, but enough survives for it to be identifiable. The hyphens indicate runes of which traces survive and which can be counted, but which can no longer be identified. The two complete words, hitir and stin, could both be read in a number of different ways, as some runes represented more than one sound in the spoken language (the i-rune could also be used for e and ei, for example, while the b-rune might be used for words beginning with both b and p in Old Norse). hitir might therefore be read as the Old Norse verb heittir ‘heats’ or as heitir ‘is called’, and stin might be the noun steinn ‘stone’ or the personal name Steinn, but there are other possibilities, especially given our lack of knowledge of the kind of everyday language that might have been in use in Lincoln at the time. In casual inscriptions like this, names are often the most commonly found element, so perhaps the most likely interpretation is ‘[someone] is called Steinn-’, even if we don’t necessarily understand why this might have been carved onto a cow’s rib. However, we only have to think of the kinds of random doodles that we might make with a pen when, say, bored or only partly concentrating (while on the phone or watching TV, for example) to realise that not all written texts necessarily have to be in complete sentences or indeed make sense! Carved on a small piece of bone that would most likely have just been lying around after a meal, the rune carver may simply have been amusing themselves or practising or even absentt-mindedly carving words that were being spoken at the time. This inscription is nevertheless valuable to historians, because it reminds us about the kind of everyday uses of language and writing which – more often than not – simply disappear from the historical record. Much of what survives from the past has been deliberately preserved and so represents something that was important or unusual or particularly valued, for whatever reason. Before archaeological excavations started to uncover hundreds of casual inscriptions like this across Scandinavia, it was thought that the Vikings mainly used runes for carving into stones and monuments to commemorate their dead, but now we know that this was not the case. Then, as now, often everyday texts and objects are discarded because they are so very common, and therefore considered unimportant or not worthy of preservation – think, for example, of post-it notes, shopping lists, or even school-work. This rune-inscribed rib from Lincoln therefore provides us with valuable evidence of the everyday use of runes in this part of the Viking world and, like place-names, is another reminder of the distinctive culture that Scandinavians brought with them to the East Midlands.