Everyday Writing in Runes in Lincoln

Dr Katherine Holman, Associate Lecturer, Open University

Posted in: East Midlands, Viking Age

(c) Christer Hamp, 2011, courtesy of The Collection, Lincoln

Lincoln, in the first half of the tenth century: a time of intense political, social, and economic upheaval, with the English kings of Wessex battling to regain control of one of the last strongholds of Scandinavian power in eastern England. The late ninth century had seen the ‘Great Army’ of Vikings, which had arrived in England in 865, switch its energies from raiding to permanent settlement, the start of a process of colonisation that left a lasting imprint on the street-names of Lincoln and the place-names in the surrounding countryside. As the English gradually regained control of parts of the southern Danelaw in the early tenth century, drawing ever closer to Lincoln, the town’s Viking leaders looked to the North and the support of the powerful Norse dynasty established in York by Olaf Guthfrithson, who also ruled Dublin in the west.

In the lower city, close to Brayford Pool and the River Witham, lie the halls and houses of the craftsmen and merchants who had followed in the wake of the first Scandinavian settlers, turning the town into an important and prosperous trading centre. In one of these houses, we might imagine a man, sitting next to the warm hearth, eating. Hungrily he strips all the flesh from the cattle ribs and, when finished, picks up his knife and starts cutting into the smooth, flat surface of one of the ribs, listening idly to the story that his brother is telling to the children, occasionally staring into the flames of the fire. As he listens, drinking ale from his leather cup, he fills the surface of the rib with the runic letters that had been taught to him by one of the men he’d worked alongside in Norway

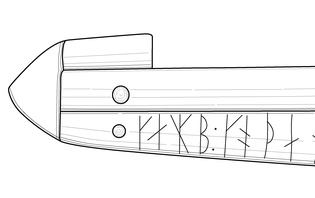

Less well known than the rune-inscribed comb-case also found in the city, this fragmentary inscription on a cattle rib – found in disturbed deposits in St Benedict’s Square, Lincoln – doesn’t contain a clear message that can be understood today. The rib is about 10 cm long and 3 cm wide at its maximum extent. It is fragmentary, missing its top half before the first word divider in the inscription, as well as the end of rib and possibly, therefore, the end of the inscription. The runes are inscribed from left to right along the length of the rib and say:

![]()

(b) – – – – – l x h i t i r x s t i n x

As can be seen from the photograph above, the tops of the first few runes are missing because the bone is broken there. The brackets around the first rune indicate that the rune is incomplete, but enough survives for it to be identifiable. The hyphens indicate runes of which traces survive and which can be counted, but which can no longer be identified. The two complete words, hitir and stin, could both be read in a number of different ways, as some runes represented more than one sound in the spoken language (the i-rune could also be used for e and ei, for example, while the b-rune might be used for words beginning with both b and p in Old Norse). hitir might therefore be read as the Old Norse verb heittir ‘heats’ or as heitir ‘is called’, and stin might be the noun steinn ‘stone’ or the personal name Steinn, but there are other possibilities, especially given our lack of knowledge of the kind of everyday language that might have been in use in Lincoln at the time. In casual inscriptions like this, names are often the most commonly found element, so perhaps the most likely interpretation is ‘[someone] is called Steinn-’, even if we don’t necessarily understand why this might have been carved onto a cow’s rib. However, we only have to think of the kinds of random doodles that we might make with a pen when, say, bored or only partly concentrating (while on the phone or watching TV, for example) to realise that not all written texts necessarily have to be in complete sentences or indeed make sense! Carved on a small piece of bone that would most likely have just been lying around after a meal, the rune carver may simply have been amusing themselves or practising or even absentt-mindedly carving words that were being spoken at the time.

This inscription is nevertheless valuable to historians, because it reminds us about the kind of everyday uses of language and writing which – more often than not – simply disappear from the historical record. Much of what survives from the past has been deliberately preserved and so represents something that was important or unusual or particularly valued, for whatever reason. Before archaeological excavations started to uncover hundreds of casual inscriptions like this across Scandinavia, it was thought that the Vikings mainly used runes for carving into stones and monuments to commemorate their dead, but now we know that this was not the case. Then, as now, often everyday texts and objects are discarded because they are so very common, and therefore considered unimportant or not worthy of preservation – think, for example, of post-it notes, shopping lists, or even school-work. This rune-inscribed rib from Lincoln therefore provides us with valuable evidence of the everyday use of runes in this part of the Viking world and, like place-names, is another reminder of the distinctive culture that Scandinavians brought with them to the East Midlands.