Watling Street, the Danelaw and the East Midlands, part 2

By Dr Kathy Holman, Associate Lecturer, The Open University

Posted in: East Midlands

If you’ve not read the first part of this blog post, you can find it HERE.

Why, in 1013, was the Danish king, Svein Forkbeard, able to rely on the support of what is described as the here – the raiding army – north of Watling Street, long after the ninth-century Viking armies had dispersed and settled, and northern and eastern England had apparently been integrated into the kingdom of England?

It seems that the reality on the ground was rather more complex than Alfred’s successors would have us believe. For example, Edward the Elder issued a law code which clearly distinguishes between the rules on compensation ‘herein’ (in his own kingdom) and in the north and the east, the latter of which were instead determined by ‘the provisions of the treaties’ (in the plural). This clearly reflects the fragmented political landscape within these areas, at least before Edward’s campaign of 917. Edgar – while proclaiming his rule over a ‘united’ England – also allowed his Danish subjects considerable legal freedoms: ‘there should be among the Danes such good laws as they best decide on’. It is interesting to note that the first reference to distinctively Danish laws operating in England is found in a legal code issued by Archbishop Wulfstan of York in 1008, just a few years before Svein landed in Lincolnshire. In this code, the legal process for a man defending himself against charges of plotting against the king (at this time, Æthelred II) is said to be different ‘for those under Danish law’. Æthelred II also issued a separate legal code for the Five Boroughs of Nottingham, Leicester, Lincoln, Stamford, and Derby a little earlier, around 997. Although the areas covered by this document were considered to be part of England and under the rule of the English king, much of this law, known as the Wantage Code, aimed to extend English legal practice into the Five Boroughs. This suggests that legally, at least, important differences remained between ‘England’ and the ‘Danelaw’, which are underplayed in sources associated with the royal court of Wessex.

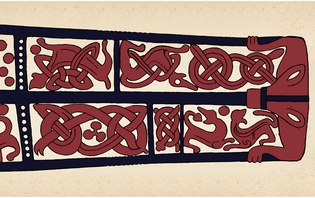

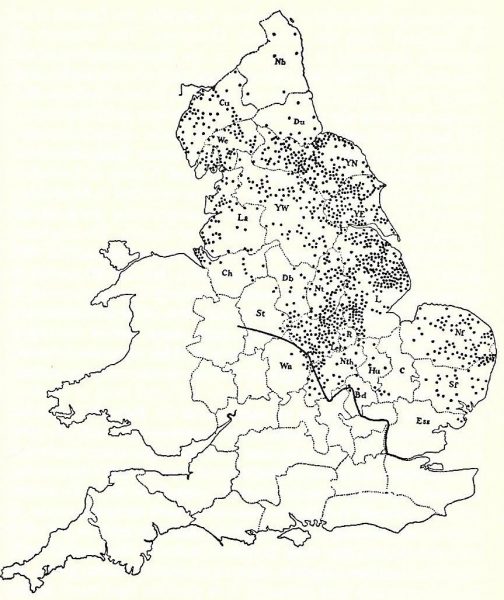

Map showing the distribution of Scandinavian place-names and the line of Watling Street (from A. H. Smith (1956) English Place-Name Elements. Nottingham: English Place-Name Society)

The place-name map bears perhaps the clearest witness to the importance of Watling Street as a dividing line between English and Scandinavian zones, showing how very few settlements with Scandinavian place-names can be found south of its line. This seems to suggest that – whatever the number of Scandinavian settlers – at the time when most of these names were given, Watling Street must have operated as some kind of border, whether that was formally established through treaties or informally observed. This is perhaps not surprising, given that there is plenty of evidence for roads being used to delimit estate and parish boundaries in the Anglo-Saxon period. One of the difficulties in using place-name evidence to understand Viking settlement is that much of the evidence for Scandinavian place-names (and indeed for place-names in general) is first recorded in Domesday Book, William the Conqueror’s record of the land-ownership, taxable values, and population, that was assembled in 1086. This makes it difficult to know exactly when the names were given, and they therefore can’t specifically be linked to the period after the conquest of Mercia in the ninth century and before the re-conquest of the Danelaw. But what we can say is that the place-names certainly suggest that the language of the people living to the north of the line of Watling Street was heavily influenced by ‘the Danish tongue’ in the period before the late eleventh century when Domesday Book was compiled and, on the basis of Svein Forkbeard’s campaign in 1013, it seems likely that this division was already clear at the beginning of that century. It is nevertheless important to remember that, even in the areas lying to the north of Watling Street, between a half and two-thirds of place-names are English. The communities that were established in the ‘Danelaw’ can’t be easily defined as ‘Danish’ or ‘English’ or even ‘Anglo-Scandinavian’ – common sense suggests that there must have been considerable local variation, with there likely to be some pockets of heavily-Scandinavianised areas and others that were less affected.

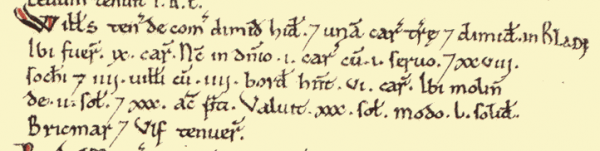

Domesday entry for Blaby, Leicestershire. Place-names ending in –by are usually Scandinavian in origin. This estate’s population consisted of four villagers, four smallholders, one slave, and twenty-eight freemen. Available at: http://opendomesday.org (c) Professor John Palmer and George Slater, CC BY-SA 3.0

Domesday Book also reveals another clear difference in communities lying to the north of Watling Street in the late eleventh century: the proportion of people described as ‘freemen’ or ‘sokemen’ –essentially free peasants – as opposed to unfree cottars, bordars, and villeins. The Midlands counties of Warwickshire, Leicestershire and Northamptonshire formed a single administrative ‘circuit’ used by the Domesday commissioners, but while there are very few freemen recorded living on estates in Warwickshire, to the south of Watling Street, the numbers jump dramatically as soon as Watling Street is crossed, with freemen forming an important element in Leicestershire’s recorded population. In Northamptonshire, which is bisected by Watling Street, the same increase in the free population can be seen in the Domesday entries for estates lying to the north of Watling Street. An earlier generation of scholars, led by Sir Frank Stenton, saw the greater number of freemen in districts that had been affected by Scandinavian settlement as the descendants of huge Viking armies, who had hung up their axes and settled down to farm in the English countryside in the ninth century. Although this has long been rejected as too simplistic by historians, the distribution of these free peasants certainly suggests important social and legal conditions operated north of Watling Street, which is also hinted at in the earlier references to specifically Danish laws in northern and eastern England. As such, this evidence illustrates how Watling Street continued to mark a dividing line at the end of the eleventh century. Politically, legally, socially and linguistically, the East Midlands occupied a frontier zone, the importance of which continued to resonate through the Norman period.

A view up Watling Street, (c) K. Holman 2018

Useful sources:

John Baker and Stuart Brookes (2013) Beyond the Burghal Hidage: Anglo-Saxon Civil Defence in the Viking Age. Leiden: Brill.

Gillian Fellows-Jensen (1978) Scandinavian Settlement Names in the East Midlands. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

David Hill (1981) Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell.

Katherine Holman (2001) ‘Defining the Danelaw’ in James Graham-Campbell et al. (eds) Vikings and the Danelaw. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 1-11.

Anna Powell-Smith and J. J. N. Palmer: Open Domesday. Available online: http://opendomesday.org

Pauline Stafford (1985) The East Midlands in the Early Middle Ages. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

Michael Swanton (transl. and ed.) (1996) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: J. M. Dent.

University of London – Institute of Historical Research / Kings College London (2018) Early English Laws. Available online: http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/

Dorothy Whitelock (ed.) (1955) English Historical Documents c. 500-1042. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.